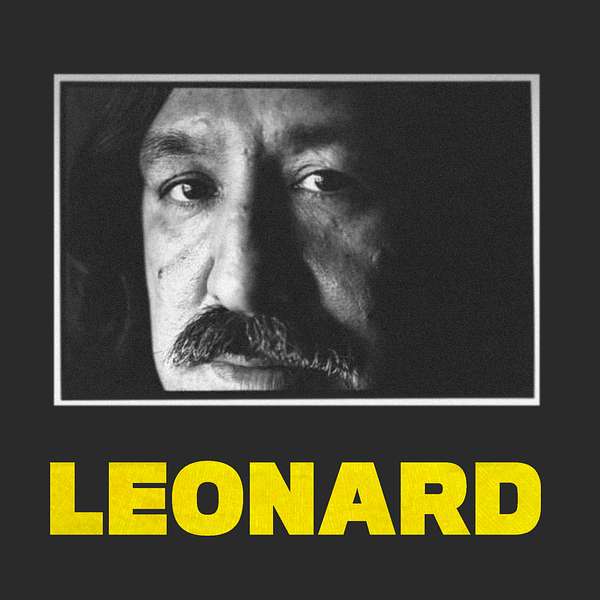

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

In 1977, Native American activist Leonard Peltier was sentenced to consecutive life terms for killing two FBI agents. Then in 2000, a Freedom of Information Act disclosure proved the Feds had framed him. But Leonard's still in prison. This is the story of what happened on the Pine Ridge Reservation half a century ago—and the man who's still behind bars for a crime he didn't commit.

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

Coincidental Witness

In June, 1975, reporter Kevin McKiernan traveled to South Dakota to cover the trial of AIM leader Dennis Banks who was standing trial for his role in the 1973 Custer Courthouse Riot. But as the hearing got underway on June 26, word spread that shots had been fired 100 miles away on the Pine Ridge Reservation between Federal agents and members of AIM. So McKiernan jumped in his truck and raced into the center of the firefight.

Ep 5: COINCIDENTAL WITNESS

Kevin McKiernan

I’m at the BIA roadblock. I can see the house. It’s surrounded by the FBI. This is as far as I’m able to go. I’ve been able to get through two roadblocks.

VO

This is NPR reporter Kevin McKiernan on the site of the Jumping Bull shootout on June 26, 1975.

Kevin McKiernan

There’s an ambulance here. There are several ambulances. One of them just took off in the direction of the final FBI outpost around the surrounded house. There are shots in the distance. This is the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation near Oglala. It’s a very hot summer afternoon. There are at least several Indians holding the building.

Kevin McKiernan

Sometimes in the distance I can hear little snitches and snaps of BIA radio transmissions and it appears that the current tactic is to try to get close enough to the house to assault it with gas.

Kevin McKiernan

High caliber bullets. <GUNFIRE> There it is again. Ricochets. Sounds like automatic fire. The BIA has told me I better move back. They’re still behind their car. Those sound like high caliber bullets. I’m down behind the back bumper of my truck. At this rate there is surely going to be some blood spilled here.

VO

You’re listening to LEONARD: a new podcast series about Leonard Peltier, the longest-serving political prisoner in American history.

I’m Andrew Fuller. And I’m Rory-Owen Delaney. We’ve spent the last year working to share Leonard’s story with a new generation of people: who he is, how he ended up behind bars, and why we believe he deserves to go free.

In this episode we travel to Santa Barbara to visit with filmmaker and journalist Kevin McKiernan who, as a young reporter for NPR and a stringer for the New York Times, found himself in the thick of the action on Pine Ridge back in June, 1975.

During a career spanning 6 decades, Kevin has covered some of the world's most troubled regions, from El Salvador to Iraq, from West Africa to Afghanistan and Syria. In 1976, he was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Pine Ridge.

We’ve heard portions of Kevin’s interviews throughout this series—with Cecilia Jumping Bull, Angie Long Visitor, Kendall Cumming, and Dick Wilson.

And today, we’re following Kevin behind the Bureau of Indian Affairs barricades in Oglala where he reported from underneath his truck while bullets whizzed over his head.

But first, we’re going to back up a bit. It seems almost impossible that Kevin just happened to sleep at the Jumping Bull ranch the night before the shootout. Until you know a bit more about his career.

Kevin McKiernan

So what can I tell you? <LAUGHTER>

Kevin McKiernan

I got into radio kind of late. And the way that I got interested in this story was I was living in Minneapolis, St. Paul, where the American Indian Movement started and was quite active. And back in those days, I was a community organizer and I ran into the American Indian Movement. So I started, uh, actually shooting pool with them in bars, on Franklin Avenue, which was in Minneapolis, sort of the reservation, the concrete reservation. And they started to see the living conditions, which I had never encountered in my life and started hearing the reports of what was going on next door in South Dakota, including a lot of violence. And I was hearing from people that I knew, uh, Indian friends or acquaintances, that there were big changes in the wind.

Kevin McKiernan

And, and I, frankly, I thought it was bar talk to some extent, but I knew that something was going to happen. So that's how I had a friend who worked at a radio station, a public radio station. And she said, well, if you’re really interested in this story, I can get you a press pass and you'll have to flip the station a few of your reports in return. And then eventually I was hired and I worked for public radio for three years.

Kevin McKiernan

The American Indian movement was really on a roll at that time. And they put together the Trail of Broken Treaties and drew hundreds of automobiles full of probably a couple of thousand people altogether to Washington during election week when Nixon was running for his second presidency. And they were able to leverage a lot of changes and a lot of controversy by taking over the Bureau of Indian affairs and carting away, a lot of papers which shed light on what was going on in Indian country. And also they received travel funds so called of $66,000 to leave Washington DC and take away this, uh, uh, taint on the election in the eyes of the Nixon administration. That's the last thing that Nixon wanted at, during that week. And, uh, but that later would dog the American Indian Movement, and some people called it a, a payoff to leave town.

Kevin McKiernan

The American Indian movement was founded in Minneapolis and the leaders, the founders of the American Indian Movement had all been in prison, except later Russell Means, who became a leader later. But at the time the American Indian Movement was mostly the Ojibwe tribe and the founders like Eddie Benton, Dennis Banks, and Clyde Bellecourt, George Mitchell. All of them had been in prison and they all had experienced similar abuse.

Kevin McKiernan

And in prison, they had identified a spiritual need that Indian people had, what was lost. And that need had to do with the reservations. None of these guys were living on the reservation. They had been city-fied, but they had come from, or their parents had come from the reservation during the termination era in the fifties and sixties.

VO

The termination era, from the mid-’40s to the mid-’60s, was a policy in which the Federal government sought to move Native Americans off their reservations—and, quote, “assimilate” them into society. To leaders of the American Indian Movement and other indigenous peoples trying to maintain a connection with their culture and history, this was yet another form of dispossession and erasure.

Kevin McKiernan

They started going back to the reservation on weekends and sitting at the feet of medicine men like Crow Dog and Black Elk and others on different reservations and started to learn about who they were and making that connection, that rural connection, that reservation connection, that land connection is what really changed the movement because now they had a spiritual basis, not just a military or activist one, and that made it different from other organizations, made it different from the civil rights movement.

Kevin McKiernan

You know, termination, um, was sold as a policy by the government of assimilation and giving Indians a chance. But for Indian people, they saw termination as a land grab. And, um, it was an utter failure.

Kevin McKiernan

So, here is the sequence. In November of 1972, you have the American Indian movement trail of broken treaties taking over the Bureau of Indian affairs in Washington. You had the killing of Raymond Yellow Thunder in the border town, near Pine Ridge. Then you had the riots in Custer after the killing, outside the bar of Wesley Bad Heart Bull. And then two weeks later, you've got the Wounded Knee occupation, which becomes the longest civil disorder in American history at 10 weeks, 71 days.

Kevin McKiernan

After what took place in Washington, the American Indian movement was really on a roll. Following the takeover of the BIA building. And Russell Means, according to Wilson, called him, Wilson up, and said, get your pigs together. Quote unquote, we're coming to have a victory dance at the town hall there in Pine Ridge on the reservation.

VO

The Wilson Kevin’s referencing here is Tribal Council Chairman Dick Wilson—the self-dealing reservation president who oversaw the Reign of Terror on Pine Ridge that left 64 AIM members and supporters dead between 1973 and 1975.

Kevin McKiernan

And Wilson responded by saying no way you're banned from the reservation. You cannot come onto the reservation at all, much less, have a victory party. And so the sides were pretty much declared at that point. And Wilson went on to get his tribal council to outlaw meetings of AIM on the reservation. And a meeting was, uh, I think was described as anything more than two or three people together who were perceived to be American Indian Movement members.

Kevin McKiernan

So the sides were drawn at that point between Wilson and the American Indian movement.

Rory

The American Indian movement had been invited by traditionals into Oglala and into Pine Ridge, right based on, on the, on the rate of terror and this sort of thing?

Kevin McKiernan

Right before the occupation of wounded knee, there was an attempt by the civil rights group of mainly traditionals called OSCRO, the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization, to impeach Wilson. And so this effort, very controversial effort to impeach Wilson failed when Wilson presided over the hearing himself. And, in the opinion of the American Indian movement supporters, terrorized those on the council, who were Wilson adversaries.

Kevin McKiernan

So when that failed, then the American Indian Movement appeared before a group of traditionals on the reservation. And they were asked then to go into Wounded Knee and to make a stand. And this took place at a little building outside of Pine Ridge. By this time by the way, Wilson had succeeded in getting the U.S. Marshals under his declaration of emergency to come to the reservation and to defend him against the American Indian Movement. And so they set up a machine gun on the top of the Bureau of Indian affairs building, the tribal council building on a tripod. And, uh, I remember hearing from people who saw that, that they would walk by and look up at that machine gun on the tripod and the blue suited marshals and say, Hey, how's that roofing job going?

Kevin McKiernan

You know, and they'd kind of tease the Marshals on top of the building, but this was definitely a lockdown. This was a militarized zone in Pine Ridge. And so the traditionals warned the American Indian Movement that if they tried anything in Pine Ridge, it would be suicide.

VO

But AIM refused to be intimidated. Instead of acquiescing to Wilson, they challenged him directly.

Kevin McKiernan

They were going to a pow wow to, to, uh, to celebrate something, uh, in Porcupine, which was on the other side of Wounded Knee. And there were, you know, probably 75 cars had to pass through Pine Ridge and Pine Ridge was girded, ready for an action there. All the cars simply go through Pine Ridge and make their way in the direction of Porcupine.

VO

Porcupine, you may remember, is the Pine Ridge district adjacent to Oglala.

Kevin McKiernan

But before Porcupine comes Wounded Knee and, and the plan, not announced publicly, went into effect then, and they took over the village. And by the next day, uh, FBI agents were there, uh, state police were there, County police were there. Uh, the FBI was there and, uh, the siege was on.

Kevin McKiernan

So Wounded Knee lasted 10 weeks. And after three or three or four weeks, the government cut off the media. And, uh, the government felt this was cutting off the oxygen to the AIMsters who had a platform and were treated somewhat royally by the international and national press and made daily forays in to get the latest statement. And so the occupation was kept alive in the eyes of the government, by the fact that the roads were open and it was okay for reporters to come in and out. So the media blackout changed all that. And I had just arrived on the scene and launched my new reporter career, so to speak. And now I said, well, what do I do, you know? And so I decided to go in the back way and I went to a neighboring reservation, to Rosebud, and I met people and I found a way to come in the back way, walking over land, which was somewhat arduous. It was at night and by then the military was secretly running the operation around Wounded Knee. The 182nd airborne was there. Officers who had never taken off their uniform, suddenly were acting as civilians. And they were kind of sneaking around and running everything. They had tripwires, the kind used against the, the Viet Cong that they had strung all around Wounded Knee. And, uh, the, these were set off when you went through them. So it was difficult. There were numbers of people who got only as far as the woods and didn't get into Wounded Knee until a day or two later.

Kevin McKiernan

They just had to wait, uh, hungry and cold because they got caught in the middle when the sun came up. So I was able to get in that way. And once I got in, I thought I'd be there for a couple of days, and it would all be over. And indeed when these negotiations started and, uh, the traditional chiefs and AIM leader Russell Means were sent to Washington for a promised treaty meeting. Um, all the television networks announced that the Wounded Knee siege was over. But it wasn't, because when they got to Washington, the White House changed its tune and said, you know, this meeting that you were going to have with the top officials in the White House is off because you're still pointing guns at us. But AIM understood there would be a mutual stand down of arms and that didn't take place. So the agreement fell apart. And then the government really started to turn up the pressure. And that's when the, when people were shot, some 18 or 20, and a couple of people were killed and the water was cut. The electricity was cut. And as, uh, the head of the U.S. Marshalls, Wayne Culver, put it, uh, we're going to change their lifestyle.

Rory

After Wounded Knee, this is when the civil war on the reservation got really bad?

Kevin McKiernan

Yeah. There were a lot of, um, of grudges on the part of the, of the Goons, uh, Wilson's so-called auxiliary police who felt they had been sidelined with all the publicity about AIM and all the publicity about the traditionals and so on. And so it was payback time and there were, there were some five or six dozen murders that took place. And then the controversy about whether or not they had been adequately investigated by the FBI.

VO

By the way, if you’re just tuning in, go back to episode 3 of this podcast: Treaties, Goons, and G-Men, Part 1, where we dig into Dick Wilson’s corrupt administration—and the 64 murders his supporters are responsible for.

Kevin McKiernan

I first met Dick Wilson in the period of time when I was going in on a daily basis. Once you were cleared by the FBI and the justice department, you could go in, in, uh, you know, in the first thing in the morning and then come out before dark. Uh, and as long as your gas hadn't been siphoned, which of course it was, you were likely to get back on the list for the next day. And, uh, I learned by the way, that the way, if you're dealing with another wounded knee -- keep this in mind -- park your gas cap next to a building because it's hard to siphon that way. That's a little tip for future Wounded Knees.

DICK WILSON

You can twist my statements around to sell copy, every damn one of you do it.

VO

That’s the voice of Pine Ridge President Dick Wilson. In both this interview, and the interview we excerpted in episode 3, Wilson’s voice drips scorn—both for the activists and the media.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, I don't twist anything. I will, it's not a printed medium. Of course it's an electronic.

DICK WILSON

Forget it fella, forget it.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Is there any possible way that I could speak with you? Uh, I'll do just about anything you'd like to...

DICK WILSON

I had a fuss with NBC and CBS right on the goddamn street yesterday morning filming three of my local drunks. I thought that was ridiculous. Say I'm violating the freedom of the press. Well, by golly, you guys all try me. See if I can't violate it.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, it would be unfair for me to have interviewed anyone else, Mr. Wilson, and not to interview you.

DICK WILSON

Obviously you're all gonna tell it like you want to anyway. So what good is an interview?

DICK WILSON

I’ve put up with this shit for 3 and a half years… Let me tell you something real quickly here. And you can let it sink in over the night. I think that you people from the news media precipitate, all of these murders that are happening around here.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Precipitate the murders?

DICK WILSON

Goddamn right.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Um, could you elaborate a little bit on that?

DICK WILSON

Yeah, because you don't tell things like they are. Y'know, there ain’t a goddamned one of you said anything about 500 houses being built here. None of you said anything about three new factories. Ain't none of you said anything about 55% unemployment rate, you know, all you're worried about is death and violence.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, I'm interested. I haven't said anything about the factories because I'm not aware of that, but I have said something about the unemployment.

DICK WILSON

See, you don't give a shit about that.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, the unemployment you mentioned, I have spoken about that. I can't say that honestly, I have about the other. No, because I don't have enough information on that. And that's one thing I think that you could help to provide in the interview. In fact, if it would help, um, I can submit the questions, written questions you don't want advanced you and I'll come back in an hour or so...

DICK WILSON

I've been through this for three and a half years.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, if I go back to my editor, the only thing he'll say to me is not that he's going to cut my material, but he's going to say, how could you possibly go to that reservation and not talk to the tribal chairman?

DICK WILSON

Well tell him you talked to me and I told you to go jump.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

I don't know if he'll buy that, to tell you the truth.

DICK WILSON

You know, that's what I'm telling you in effect...

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

To go jump?

DICK WILSON

You know, you're going to tell it the way you want to anyway. So interview me...

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Not if I have you telling what people say, you say in your own words, instead of having people tell me what you say. That seems to be the greatest problem. You know that everyone has an idea of what Dick Wilson says. I'd like to hear it from Dick Wilson.

DICK WILSON

Well, you're hearing it right now. I think you guys are a bunch of shit.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, one of the advantages that we have is that I can use your voice. I don't quote you in the newspaper. I use your voice. You were speaking. And I think this is one of the advantages of radio.

DICK WILSON

You wouldn't tell that, if I told you in an interview that you were a bunch of shit, you wouldn't tell that.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

If you'd say that in an interview, that I'm a bunch of shit. I promise you I will put that on the air. And FCC or no FCC.

DICK WILSON

What'd you say your name was?

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

McKiernan.

DICK WILSON

First name?

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Kevin.

VO

After the break, Kevin tells us how he ended up on the Jumping Bull ranch the night before the shootout.

PETER COYOTE

This is Peter Coyote, and you’re listening to “LEONARD.” For decades I’ve been advocating for Leonard’s freedom, using my celebrity as a screen and stage actor to educate the public about his case. Together we can right the injustice that has kept Leonard behind bars for 44 years. Together we can finally send Leonard home to his family and friends to live out his days painting, writing, and fixing cars. To help today, you can sign the new clemency petition at freeleonardpeltier.com. You can also purchase artwork and merchandise to support Leonard’s legal defense at whoisleonardpeltier.info, and send messages of support for Leonard’s clemency to @realdonaldtrump. We know the President loves Twitter, so let’s keep Leonard in his timeline and mentions. Hashtag Free Leonard Peltier.

VO

On January 27, 1973, Darrell Schmitz—a white man who’d already been arrested for assaulting a Native American—stabbed Wesley Bad Heart Bull to death in Buffalo Gap, South Dakota. And despite the fact that witnesses overheard Schmitz say that he was planning to, quote, “kill him an Indian,” Schmitz was charged with second-degree murder—the equivalent of involuntary manslaughter—and released on $5,000 bail.

So on February 10, 1973, AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Russell Means traveled to the Custer Courthouse in the Black Hills, with a caravan of more than fifty cars, and demanded that Schmitz’s charge be upgraded to first-degree murder.

But Custer County State's Attorney, Hobart H. Gates, refused to reconsider. And when Banks and Means tried to escort Wesley Bad Heart Bull’s mother, Sarah, into the courthouse so she could make a statement, more than 90 armed police descended on them. One officer struck Sarah in the face with his baton, and then pinned her to the ground with a nightstick across her throat.

That’s when all hell broke loose.

In the resulting riot, AIM protestors, despite being outnumbered 4-to-1, filled soda bottles with gasoline, set the Custer County Courthouse on fire, torched police cars, and burned the Custer Chamber of Commerce to the ground.

Sarah Bad Heart Bull was later convicted of, quote, “inciting a riot,” and sentenced to 1 to 5 years. And in 1975, it was Dennis Banks’ turn to face the judge. And Kevin McKiernan drove down from Minneapolis to cover the trial.

Here’s Kevin again.

Kevin McKiernan

Dennis Banks was on trial for the Custer riots that had taken place in 1973. And this was two years later and he was on trial in the Black Hills village of Custer named for the notorious general. And so he at the time was living with the Jumping Bull family in Oglala on the reservation, in the ranch that the Jumping Bulls had. I was stringing for the New York Times. And so I wanted to go down.

Kevin McKiernan

And so I drove down to the ranch. I'd never been there before. It was a sprawling ranch. And, um, in fact, um, it was a big storm. You may have heard about it that day, a tremendous storm that blew the roof off, I think the, the County courthouse. And, uh, it was a rainstorm like I've never seen before. And I was making my way down there after court that day to meet Banks to do the interview, and an old couple in a great big old Chrysler car had lost their way. And because of the rain storm, and they had blundered onto the reservation, which is something a non-Indian would, would never do in those days. And they were going along very slowly in this torrential downpour when they hit a deer, and they, they almost turned their car over, but they didn't. And I came along and I saw them by the side of the road and I saw the dead deer. And, uh, so I managed to get the car started for them. And they, they went on their way. And before they left, the man helped me, uh, hoist the deer into the back of my pickup truck.

Kevin McKiernan

And, uh, then I brought that as kind of a, a roadkill gift to the Jumping Bull family. And it was still up there during the shootout and afterwards strung up where they had started to clean it. And, uh, if, uh, if that's not a detour to your question, I don't know what is.

Kevin McKiernan

So when I got there, the rain got even worse and it was so totally muddy. The family said, you've got to stay overnight. You can leave in the morning and Banks and his entourage will be going up to the trial. I didn't go up with them, but they had, and they had left before I did, but I got up and I left about an hour, as it turned out, about an hour before the FBI agents coming on the property and the shootout starting.

Kevin McKiernan

So, uh, and that was just, um, good luck for me that I wasn't there. So I drove up to Custer and came into the trial again, I got there late in the morning. And I just sat down in the back of the, of the court, in the back of the courtroom and suddenly, um, there was all this hubbub inside the railing by the judge's bench and people whispering and talking excitedly. And then, um, the judge called a recess and banks came out of the well of the courtroom and came back to me and he said, they're shooting it out on the reservation.

Kevin McKiernan

And I knew the place that he must be talking about. It was the place he had been. And so I turned around, having spent only, you know, 10 minutes so far in the courtroom and turned around and drove back and then tried to negotiate my way through the FBI roadblocks and the BIA roadblocks. Because at that time, the FBI knew that agents were down, but they didn't know if they were dead or what the status was. So the tempers were really on edge. And I pulled up to the first payphone and I called my radio station in Minnesota. And I said, I'm going onto the reservation. I don't know. I won't have a chance to talk to you from now on. And I don't really know what's going on there. Um, and so of course in those days, there were, there were no cell phones and oftentimes no landlines on the reservation.

Kevin McKiernan

So I took off and went down there, got to this FBI roadblock and, and two guys jumped up into each open window in the cab and stuck their .38s, right at me, you know, and, uh, said, uh, you know, who are you? What do you want? And as luck would have it, my mother had insisted that I take all my junk that for years had cluttered up her garage and, uh, get rid of it, even though I was going on this trip to South Dakota. So I obliged her finally, because I had made promises and kept them before they took all these old radiators and batteries and $4 tires and fan belts and all sorts of greasy jacks and all that, and threw it in the back of my pickup truck. Now, before I came to cover the case in the Black Hills with Dennis Banks, I had gone to visit a friend of mine in Colorado, who was in the construction business.

Kevin McKiernan

And he ran a company called Magic Construction. And they were, they were pretty far out guys who carried hammers and all the carpentry tools but wore capes and smoked a lot of dope in the morning and then went to visit the unlucky homeowner. And so at the end of it, he, he said, you want a couple of signs? They're magnetic, they'll go right on the side of your pickup truck. And it said, Magic Construction. So I put one on either side. So now the FBI agents are looking over. One of them was holding a gun at me. He goes back to look, check out the stuff in the back, which I had dutifully gotten out of the garage for Mom. And then they looked at the side, they saw Magic Construction. They said, this is a good old boy. And they said to me, uh, you know, I made the case, somebody's got to report what took place in there, the truth of what's going on, blah, blah, blah.

Kevin McKiernan

And they said, well, we'll let you go to the next roadblock that's Bureau of Indian affairs. They'll never let you through. And they waved me on, you know, thinking I was a local good old boy with Magic Construction. And, uh, I got up to the next road block to the BIA. And I said, FBI has already cleared me to come through here. And I kind of BS'ed them and made it through that roadblock. And then I got to the Jumping Bulls and the firefight was big time in progress there and just got under my truck and reported for the rest of the day.

Kevin McKiernan

These federal cars continue to race up and down the roads, over the ridges, the rolling plains.

VO

This is Kevin filing from Oglala on the day of the shootout.

Kevin McKiernan

Outside of that it’s quiet. But from where I am I can see these little Indian children playing by these tar paper shacks. Horses continue to play in the meadows all around. There’s a stream here and a small little fishing pond. The FBI plane has moved out of gunshot range. Actually it’s a police plane. It’s difficult to say which division of the gov’t owns it. In fact I just heard a transmission over the BIA radio. There appears to be some problem already between the BIA and the FBI and the US Marshals. There’s some firing now. Some problem as to who has command here. This was one of the problems with Wounded Knee, and Wounded Knee is only a few miles from here. It’s the same problem on Indian reservations of jurisdiction and the hierarchy of gov’t command off the reservation, when it comes on the reservation, simply has always been a boondoggle. There’s more firing.

VO

After interviewing everyone from the Jumping Bulls to officials from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the FBI, this is how Kevin summed up the shootout.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

What few people know if anyone is what happened to provoke the gun battle, what happened during it, and what has happened since. Both gov’t and Indian reports have been severely self-contradictory. The media have printed and aired false and irresponsible accounts, and the public has been shortchanged. Some examples. Authorities first said that the two FBI agents were killed when seeking to serve warrants on four Indians wanted for kidnapping. Later this was corrected to mean that one of the four, Jimmy Eagle, was being sought at what came to be the site of the gun battle. As for the kidnapping, later when all four either surrendered or were apprehended, they were charged with assault and robbery, not kidnapping. Two weeks after the June 26th shootout the United Press Int’l reported that only three Indians were wanted for the quote “kidnapping” unquote. And the UPI report said that the dead Indian was killed after the FBI agents had been slain. But no indication of proof in that regard has ever been established. Nor has there been any proof, as the American Indian Movement contends, that he was killed before the agents, thus causing the death of the federal men. The fact that Stuntz was wearing a FBI fatigue jacket when this reporter saw him lying dead on the ground after the FBI had assaulted the buildings is inconclusive in either case. He could have taken it from one of the dead agents or it could have been put on him before outsiders were permitted into the shootout area. Additionally reports that he was shot in the front of the head also were false. The only blood I saw was underneath the FBI jacket coming down his arm and wrist. And there’s more. Toby Moran, the BIA public information officer in Pine Ridge, was quoted widely in the press to the effect that the area was an armed camp with bunkers and trenches that had been dug. The fact is there were no trenches. The so called bunkers were 30 year old root cellars which the Jumping Bull family used to preserve food. And some reports said that AIM leader Russel Means lived with the Jumping Bulls. Actually it was Dennis Banks when Banks was on trial 100 miles away in the Black Hills village of Custer where he was convicted a month later on charges stemming from a disturbance two and a half years ago.

And so very few facts have uniform agreement. What seems to be known is that Coler and Williams entered the Jumping Bull’s land shortly before noon on June 26th and died soon after. When the area was taken by the police six to seven hours later, the agents were dead and Joe Stuntz was dead. An undetermined number of individuals had escaped and the most massive manhunt in South Dakota history was underway. Whether the fugitives were a band of paramilitary guerillas as some authorities have said or whether the FBI backfired its plans to raid the area, as many local residents contend, simply cannot be known. The full truth may well lie with the three victims of the confrontation and with those who got away.

Rory

So you've interviewed Leonard?

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

I have.

Rory

Talk to us about that experience.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Well, I interviewed him in, in Marion, uh, penitentiary and I interviewed him at Leavenworth penitentiary. And I tried to interview him at Coleman in Florida where he is now and I wasn't permitted to do so. And I spent, um, 18 months trying to get in to interview him for my own film. And finally, I got a member of Congress in Washington to pressure the Bureau of Prison to even answer my request.

Kevin McKiernan

I mean, they were, they were just, uh, you know, stonewalling me, you know, doing the millennial thing...

Rory

Ghosting you.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Yeah, ghosting me, right. I didn't exist. I didn't exist. So finally they said, you can't because of security, you can't go in as a journalist. You can't go in, his friends can go in, but journalists can't go in. And of course this was in the run up to, uh, the Obama administration deciding whether to, um, cut him loose and let him let him and let him go. After 40 some years. And the Bureau of Prisons, I take it, was very afraid. And of course there was tremendous pressure from the FBI. That pressure had already worked on Bill Clinton. And despite the fact that the appellate judge who upheld his conviction, went to bat for him and wrote a letter for Clinton saying that it was in the national interest in terms of healing with Native Americans, that after all these decades, much longer than most people would have spent for murder, that he be released. And that it would be that it was very important and that the federal appellate court judge even went beyond that. He said that the FBI shared the blame for the three deaths in Oglala, the two agents and the Indian, that it wasn't only solely the Indians’ fault. It was the FBI's fault. The government should have negotiated legitimate grievances at Wounded Knee two years earlier and failed to do so and saw every grievance that Indian people had in terms of a military response. And as a result, this was inevitable that indeed—and these are my words—there were two trains on the same track coming at each other: Indians and FBI. And they were bound to collide. And that was the tragedy at Oglala.

KEVIN MCKIERNAN

Leonard Peltier is always painted as a cop killer. And in fact, as the federal prosecutors themselves have said in open court, and I was there in St. Louis when they said this, we don't know who killed the agents. So they don't know who killed the agents. And they used the theory of being a helper then who did he help? Because the other two defendants Butler and Robideau their case was dismissed in federal court, in Iowa.

[Music beat]

VO

In the next episode of LEONARD: Political Prisoner, we speak with Leonard’s lawyer, Kevin Sharp, about some of the tactics the Government employed to make what he, and other advocates, see as a fraudulent case against Leonard.

Oh, and we finally speak with Leonard himself…

A couple of corrections before we go. We’ve fixed it, but in the original version of episode four, some of you may have heard us mistakenly report that Jean Roach and Norman Brown were married. That’s incorrect. And Norman didn’t teach her how to make turquoise jewelry, either.

As Jean herself says, she aspires to represent a Lakota style in her art using natural, local materials. Some of her most popular pieces have incorporated turquoise, but as her practice has evolved, she’s endeavored to use AGITS and fairburns—minerals native to the ancestral home of the Lakota.

Go to redcloudschool.shop to check out Jean’s work. It’s worth the visit.

And finally a quick clarification from episode 3. While referencing the Supreme Court’s decision in Sharp v. Murphy we stated that an area covering roughly half the state of Oklahoma was awarded to the Muscogee Creek Nation. Well, it was also awarded to four other tribes, including the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Seminole Nations.

We really strive to get all our facts straight, and we apologize for goofing up. Thanks for calling us out on our errors!

This podcast is produced, written, and edited on Tong-vay land by Rory-Owen Delaney, James Kaelan, and Andrew Fuller.

Kevin McKiernan serves as our consulting producer.

Thanks to Maya Meinert, Emily Deutsch, and Blessing Yen for helping support us while we do what, we hope, is important work.

Thanks to Bobby Halvorson for the original music we’re using throughout this series.

And thanks to Mike Casentini at the Network Studios for his engineering assistance, and to Peter Lauridsen and Sycamore Sound for their audio mixing.

Thanks to Paulette Dough-TAY at the International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee.

And thanks, most of all, to Leonard Peltier.

To get involved and help Leonard, sign the new clemency petition at freeleonardpeltier.com. For more information, go to whoisleonardpeltier.info or find us on social media. @leonard_pod on Twitter and Instagram, or facebook.com/leonardpodcast.

This podcast is a production of Man Bites Dog Films LLC. Free Leonard Peltier!

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.