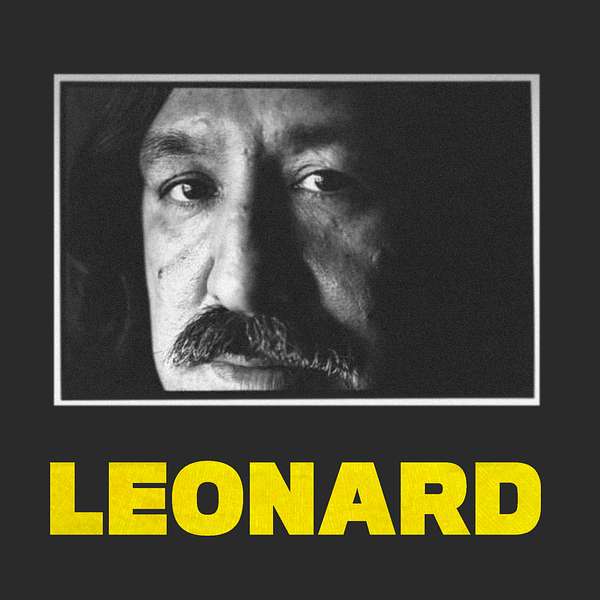

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

In 1977, Native American activist Leonard Peltier was sentenced to consecutive life terms for killing two FBI agents. Then in 2000, a Freedom of Information Act disclosure proved the Feds had framed him. But Leonard's still in prison. This is the story of what happened on the Pine Ridge Reservation half a century ago—and the man who's still behind bars for a crime he didn't commit.

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

Louise

We interview Native American author Louise Erdrich, who attended Leonard Peltier’s murder trial in her hometown of Fargo, North Dakota, in 1977. The 2021 Pulitzer Prize Winner for Fiction analyzes where it all went wrong for Peltier, while sharing how the experience affected her concept of justice, a theme which became a hallmark of her literary career. Along the way, Louise reads from her correspondence with Leonard, revealing new details about their friendship, before laying out what his freedom would mean to the Indigenous community in North America and around the world.

S2 E14: LOUISE

Louise Erdrich

The moment of the verdict is one of those emotional divides in my own life where I saw the world one way. And in an instant I saw the world in a very different way.

[MUSIC UP]

VO

That’s Pulitzer Prize winning author Louise Erdrich.

In the summer of 1977 Louise was a fresh-faced Dartmouth grad working her first job out of college in Fargo, North Dakota, when a moment of serendipity led her to attend the murder trial of Leonard Peltier.

It was a profound experience that shaped her journey as an artist.

Louise Erdrich

I listened to the evidence. I had tried to piece it together. And I couldn’t connect it.

There was no specific evidence there that said, alright, Leonard Peltier, this was his gun. This was the bullet. This is what happened. Right. So this didn’t fit together for me.

My chain came up with missing links, with nothing I could connect about that scene specifically to Leonard. You know, it would have to be specifically to him. But the jury connected those links. They made those leaps of faith in the broken chain.

Those leaps of faith representing fear, resentment, and a sense of threat, you know, all of these things.

But I didn't think that would be possible.

And when we found out the verdict, there was a sense of – I’d say that it was this crushing sense of disbelief.

There was this, this, this sort of eruption, a shout that was just like, no, no.

And, um, it took a long time for that revision of outlook to become in a sense who I was and who I tried to be for years after that.

Um, it certainly turned up. That's where I started writing Love Medicine.

In that book I think I referred to this idea that everyone that I grew up with has about justice. That it is justice, but that if you're on the other side of a wall, if you're not white, and you're not in the good people category, anything can be done to you.

Anything.

VO

You’re listening to LEONARD—a podcast series about Leonard Peltier, one of the longest-serving political prisoners in American history. I’m Andrew Fuller.

And I’m Rory Owen Delaney. We’ve spent the last four years working to share Leonard’s story with a new generation of people: who he is, how he ended up behind bars, and why we believe he deserves to go free.

This is Season 2, Episode 14, “Louise.” In this chapter we explore the Fargo trial from the perspective of one of today’s greatest living writers, Louise Erdrich.

But don’t take our word for it. Erdrich has a long list of accolades, including one National Book Award and two National Book Critics Circle Awards. She has also received the Library of Congress Prize in American Fiction, the prestigious PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.

As we were pursuing this interview, Louise added another trophy to the cabinet when her novel The Night Watchman claimed the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 2021.

Which made it more difficult than usual to book the Native American author and poet for our humble indie podcast. Because Louise doesn’t often grant media requests.

At least that was per her literary management team who responded to our initial email inquiry by asking how much money we’d be willing to pay.

We answered that we couldn't afford to make a cash offer but asked them to please deliver our heartfelt plea to Ms. Erdrich anyway.

And it worked. As soon as Louise found out what we were up to, she was in.

Which means a lot. Louise was already busy doing press for her Pulitzer and finishing her next book, The Sentence, so she had every right to say thanks but no thanks.

But she didn’t pass. She made it happen and cleared time in her hectic schedule to speak to us about Leonard in November 2021.

This was big. I mean, it was basically the literary equivalent of snagging Michael Apted.

It was an interview that we never dreamed we’d get, and when it finally took place, Louise did not disappoint.

In our last episode we analyzed Leonard’s trial from a largely legal perspective, detailing how the facts of the case were orchestrated to ensure that the jury in Fargo, North Dakota, reached a different conclusion than the one in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

In this installment a Pulitzer Prize winner paints a psychological portrait of what happened and why to try to help us make sense of this madness.

Because justice isn’t uniform. It’s not some commodity that’s the same on store shelves across the country. It’s the product of specific people within a specific environment.

It’s a job that Louise Edrich is uniquely qualified for for a couple reasons. First, because of her background. And second, because of her unique understanding of human behavior as one of the foremost writers alive today.

We also wanted the interview because while researching Season Two of this podcast, we discovered an old excerpt from PBS’s Democracy Now! where Ms. Erdrich talked about attending Peltier’s trial.

ARCHIVAL LOUISE ERDRICH

I sat through that trial as a young person. And I listened to all the evidence, and I heard it all. And there was no way that I could see that this person would be convicted. There simply wasn’t evidence. And he was convicted. He received two life sentences.

VO

That clip set this whole process in motion. But it’s short. And we wanted to hear more from Louise on the subject.

Because we knew she would spit fire. And we had a lot of questions.

Like why she was in Fargo, North Dakota, in the summer of 1977, and how she had come to attend the Leonard Peltier murder trial in the first place.

Without further ado, here’s Louise – in her own words.

Louise Erdrich

All right. So I'm Louise Erdrich, and I grew up in Wahepton, North Dakota, which is a town about 45 minutes south of Fargo.

Wahpeton has always been a small sort of insular town, and Fargo was the big city.

My mother found out that Dartmouth was admitting women and had a Native American program. Nobody believed it, but she found it in a National Geographic, and she was convinced I should go there. And I did go there.

I'd never been on a plane. I'd lived my whole life only in Wahpeton, except for visits to Fargo or Winnipeg. People love to go up to Winnipeg from North Dakota. It's so much culture, you know? [Chuckles]

And, uh, I came back after college with a bachelor of arts, and no job. I forgot to prepare for a job. They don't prepare you for a job. [Laughs] You know, I hadn't thought about it.

So, I ended up going to the big city, which is Fargo, deciding that I would become a professional poet. And, um, I worked for a small press distribution service, and I lived in a small apartment over a place called Frederick's Flowers, which is still a flower shop.

And, uh, that's about two blocks from the federal building in Fargo.

So I'm working for my friend, Joe Richardson, who has this small press distribution service, and we publish poets. And my – my greatest aspiration is to have a chapbook.

I'm in no way an activist at this point, you know, I'm just, um, I just want a chapbook. I want to be – I'm a poet.

And my poems are sort of set in the breakdown lane, because I was always in the breakdown lane.

I had these unreliable cars. And, uh, silent fields. And I guess I featured the violence of suppressed emotion in young women, let's say. [Chuckles]

So there I am, and one day in the spring of 1977, I hear, uh, what I'm thinking then are powwow drums, but they're not, they're different.

VO

In the mid 70s Fargo was a relatively small town with a population of roughly 50,000. So when Louise heard the thumping of what sounded like powwow drums coming from the street outside her office, she went to investigate.

Louise Erdrich

You know, my world, my world then is downtown Fargo. And that world we can go into later because it features lots of bars, let's say. Bars and poets.

Anyway, I go to see what's happening. And I see some people that I grew up with in Wahpeton.

One person is known as a runner. He ran with my Dad. He played basketball with my father, Ralph. I mean, he was just known as an all around athlete.

Well, I'd never seen him as, um, we, we didn't really, I didn't really see people as Indian, not Indian, native, not native, because I grew up in a place where people were kind of stirred up together.

And all of a sudden I saw him dressed slightly differently. And I saw some women I knew. A lot of women I had known or grown up with.

I don't remember everybody, but I remember shaking hands with people and kind of joining into this group.

VO

We promise not to cut in too much here but we just want to stress that when Louise sat in and observed Leonard’s trial she didn’t have any prior allegiances. She was just an impartial observer. That’s what makes her conclusions all the more poignant.

Louise Erdrich

We were gathered at that point in front of a building with tall, ionic columns, beautiful columns, beautiful limestone. Majestic building.

There are not that many majestic buildings in Fargo, but that was it. That was one.

So I heard what was happening on some level, which didn't make a lot of sense to me.

People were also dressed very, I would say humbly, you know, in windbreakers, and jeans, and old tennies. Kind of like me at first, you know, I, I wasn't part of this.

There was a few people dressed in more traditional clothing. But mostly it was people who started telling me a little bit about what was happening.

And so I went in, and I think we went through, maybe metal detectors or some sort of security line.

I'd never been through anything like that before. You know, there was, there was nothing like that in my life.

And I went in to sit down, and went into, um, it was, uh, some kind of long imposing atrium entryway, and then into a smaller, a smaller hallway, large wide hallway, and then into the courtroom.

Filed into the courtroom, and sat in the back, and sat with these people. And so that's how it started. I started going to the trial. and I don't remember at what point I had entered into the process of seeing this trial.

Rory Delaney

From what I read, it seemed like there was just Marshals everywhere, and just sort of very intimidating. Was it intimidating to enter the courtroom every day?

Louise Erdrich

Yes, it was. As I said, I'd never been through a security checkpoint before.

I'd never been in the presence of -- this sense that we had to corral these people together because they might suddenly burst out in violent – you know, in violence.

I think that was the sense in the courtroom that the Indian people, and I keep saying Indian, because that's what it, that's what everybody was at the time.

You know, now it would be, I would say Indigenous people, right?

But at the time it was Indians, the Indians had to be kept under control, and the implication of that is they're dangerous.

You could look at everybody who was, who was in that group, [Chuckles] and say, well, who's dangerous. There's a couple of people who have long hair in braids maybe.

And a few men in the Calico, the bone choker. There was one person who had, um, a jean jacket and was carrying a pipe bag.

That's it. But they're mostly women in windbreakers and sneakers.

Rory Delaney

That sounds terrifying. [Laughter]

Louise Erdrich

Yeah, it was really scary. [Laughter] But no, I, I actually have – I saved the Fargo Forum. I, I found it in this – the guilty -- the day after the guilty verdict.

And sure enough, there's a few men in, and I, I love this look, you know, like the Calico, the bone choker, the hat. I love the hat look, but nobody had a hat on in this picture.

But I'd never been to anything of this nature, where people were assembled to be part of a cause that was very emotional.

I mean, there were people in tears, and there was people, there were people who, um, who had a very deep commitment to spiritual life.

I'd been raised a Catholic. I didn't know about other people, my age, who were involved in native spiritual life.

My grandfather was. He was part of the Mahday, but he was one of the very few people on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, who had that belief.

He was an – he was an Ojibwe speaker. He prayed for me. He named me.

But I didn't know there were, there were other people. I mean, this sounds crazy now because, well, everybody knows, but I didn't know.

I felt, um, I felt that I belonged with the other people. And there were some people I knew, so I didn’t – I had a different connection.

VO

Like Leonard, Louise is Ojibwe and an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, a connection that we’ll explore in more detail later in this episode.

Louise Erdrich

So, um, I began going to the trial and listening, and I guess I tried to form for myself without knowing anything about what happened in Pine Ridge. I had a very minimal, you know, knowledge of what had happened.

So I was purely trying to figure out whether Leonard Peltier was guilty, or not guilty. You know, this is what I was, of course, because this was the trial.

This was part of what I was listening for. But also I was – I was surprised when, um, I think I saw the, the bus with the jurors, the jurors getting onto a bus.

And it seemed to me that the windows – that they couldn't see anyone that they got into the bus. And I guess they were going off somewhere to, you know, be sequestered, whatever.

VO

The jurors couldn’t see out of the windows of the bus because they’d been papered over as part of the sequestrestation process.

They were told it was for their safety but really it was a ploy by prosecutors to keep the jurors from seeing that Leonard’s supporters were just as human as they were.

Louise Erdrich

Anyway, it surprised me that the jurors couldn't see the people.

They could probably, you know, they could see them, of course, in the courtroom.

But I thought, oh, so they must feel a little like me. Like, this singing -- this drumming – what does that mean to me?

To me, it meant, of course, oh, this is something -- it's resonating for me. It's something I may have always needed or wanted.

And you know, because I should say, you can't see me now, but you'd never think I'm an, uh, uh, an American Indian, a native person.

You know, I'm, I'm like a white, a white person, a white looking person.

I have dark hair, brown eyes, but, you know, so I knew what they must be feeling because I've been around.

I've been raised with people in North Dakota who had this certain feeling about Indians, and that must've been really scary to them.

[FADE UP AIM SONG]

You know, suddenly hearing their drumming. W -- what? They're drumming. It must be like war drums or whatever.

You know, these were songs, these were spiritual songs, songs of healing, songs of peace, songs of appeal to the greatness of spirit, you know. These were what the songs were. And I knew I knew that.

But what they were hearing was something very different.

And so, you know, to set the scene of what it was like for people at that – for, for, for white people at that time in that place. Okay.

What I would always hear was, oh, she's a good Indian. He's a good Indian, or not a good, bad Indian. Good or bad. Good Indian or bad Indian.

Bad Indians made trouble, and a Good Indian was someone, oh, who is working as a janitor.

They would have – white people had some, um, contact with good Indians who worked in very low level jobs, you know, something that was non-threatening.

Native American people lived largely hidden lives, you know. Native American people had always been quiet.

My grandfather, he was an incredible power force, an activist who saved his people from the policy known as termination, but he was quiet. He was friendly. He was funny. You know, part of his power came from being two things at once.

VO

Louise’s grandpa Patrick Gourneau worked as a night watchman at a local factory, so that he could spend his days fighting the proposed termination of the Turtle Mountain Reservation in his capacity as tribal chairman.

Gourneau is the inspiration for the protagonist of her Pulitzer Prize winning book THE NIGHT WATCHMAN.

Louise Erdrich

So, at the time, the other bad Indian was the drunk Indian, right?

So, yeah, I was at a lot of bars. The Pink Pussy Cat, which featured a giant winking sign of a pink pussy cat. The Roundup, a cowgirl swinging a lighted Lariat.

I mean, I miss these bars. They were torn down. And it's now a parking lot where they were. Um, so these bars and taverns were about three or four blocks, I think from the federal building, maybe five.

They were in a, a world that white people would drive through it if they – unless they were part of the world and wanted to drink [Laugh], you know?

So there were a lot of white people stumbling around, and there were Indians stumbling around on the streets.

Fargo's a very small downtown, and all these places are, um, within maybe six blocks of the railroad station.

And Fargo looks a lot like it did in 1977. I think at the time when urban development happened, for whatever reason, they only got rid of the place where, where, um, people drank. You know, that was the, that was the awful spot. So they got rid of it.

But they kept the rest of the downtown, whether it was for lack of money or a wish to keep it the way it was. I don't really know. But Fargo looks a lot the same.

But that's how people, how white people would have seen Indians – as people who were stumbling around.

Or now this new category, which was angry Indians, or bad people who were causing trouble, who were stirring things up.

Being an AIM, you know, that was scary. That meant you were a bad Indian.

And white people are only, um, a couple of generations at that time away from the, um, Indian wars. They're still scared.

You know, they have this conception that Indians could rise up somehow. [Laughs]

And, the fear is in this jury. And it's being fanned by this idea that you shouldn't look at anyone because if people had looked out, they would've seen, as I was describing, some very humble people who wanted justice.

They, you know, they, they were singing. So I guess that was, and the drum, all they heard was, was that part of it, you know.

Rory Delaney

It was the fear of the other kind of.

Louise Erdrich

A specific other. It was a specific, you know, every, it's hard for people outside of the west or Midwest to understand that that fear also has a flip side of hatred.

Because on the coasts native, Indian people, are more, um, romanticized, because the coasts succeeded in the project, which has always been a project of the United States government, of total, of almost total eradication and dispossession.

So people there don't -- often don't understand the hatreds in Northern Minnesota, in many parts of North Dakota, throughout the West, Midwest.

The hatred. And the resentment. I think that's a big part of it, too.

The attitude isn't like, oh, look, what I'm standing on really belongs to Indian people. To native people.

Um, I think when AIM started, or I don't know when the American Indian Movement, um, made the first speech, “We are your landlords, right? And the treaties are basically, and the agreements are basically rent.”

Well, that started, started in my mind, at least with the American Indian movement.

And, um, I believe it began to trickle throughout people's attitudes – maybe in a very limited way in places that are close to reservations, and people feel very threatened.

This idea that somehow Indians are getting something for nothing. That's very deep. Like, how can they complain? [Laughter]

This is, this is the attitude. How can they complain? Look what they're getting. They're getting a free ride. And look it -- the government gave them this land. That's the attitude.

VO

That was the attitude expressed by Shirley Klocke, who was allowed to remain on the jury in Fargo despite admitting to prejudice against Native Americans during voir dire.

We asked Louise for her general impressions of the jurors.

Louise Erdrich

They were all white people, and they were the sort of people I would have gone to church with. Um, they were people I grew up with. They would have been neighbors, people in town, you know.

And, um, it didn't surprise me that everyone was white, because, I guess because white people were always in charge or always on, in official positions in North Dakota. So I was not surprised.

In a very few places, um, native people would be in charge, but not in something like this courtroom, which was imposing, and a lot of dark woods, and was a place where like all the priests, all the nuns, all the, you know, the Kiwanis club, everybody [laughter], the, um, Elks club.

All the people who were in charge of Wahpeton, they were all white. So I was not surprised.

Rory Delaney

And what was your impression of the judge, of Judge Benson?

Louise Erdrich

Well, he would have been the head of the Elks, the [laughter] Elks club or whatever.

You know, there's a clear hierarchy in my town and he would have been the police chief, the person, the judge, the person who everyone looked up to and who everybody, um, everybody believed and depended upon and who ran things. So that's who he was.

I didn't know what was really going on at the time, but I accepted all that, that the jury was white because this was North Dakota, and that the judge was in charge. I just accepted it.

Rory Delaney

So what were your impressions of the trial? You were just going in there to kind of hear both sides. And so what did you make of the– both sides?

Louise Erdrich

Well, I didn't really, I don't think I heard both sides. The defense is very foggy to me. I didn't think that the defense was– I didn't hear a lot of the defense.

I tried to piece together what the prosecution was telling the jury and the judge. And I haven't really gone back and looked through the transcript of the trial or anything like this, so I'm just giving you what at the time were my thoughts as I was hearing this.

I know there was ballistic evidence. And this seemed to me something that was, uh, it was, uh, it, it rattled like some kind of unlinked chain in my mind.

I couldn't make a connection. There was no specific evidence there that said, alright, Leonard Peltier, this was his gun. This was the bullet. This is what happened. Right.

So this didn't fit together for me, and I go in naively now that I look back, of course, but at the time, what I was looking for was some piece of evidence.

Something had to connect this person, Leonard Peltier, beyond a reasonable doubt to the killings.

And these were brutal killings.

All the killings down there at that time were brutal. And as I heard, I heard about them more and more by being around people.

And I hadn't known what it was like down there. I began to understand it.

And, of course, I connected it with what it would have been like on, um, the place I went to stay with my grandparents in the Turtle Mountains, and what that would have been like to live basically in a war zone, where some people were getting killed around you, people you loved.

What that would be like to be in that world where you were being targeted for murder, and there were guns. And I, I, I hadn't, I hadn't put that together, but that was nowhere in the trial, I mean, there was no mention of what it was like down there.

This is something I heard from people I knew, what it was like, you know?

So that was was another thing. I knew the outcome of the other trial.

So I knew the stakes were pretty high for the FBI to convict someone, because if they didn't, what would that mean?

It would mean that somebody got away with murder. That’s the thing.

I mean, somebody had to take this fall, and people had to have some satisfaction because of all those terrifying things that happened on Pine Ridge.

People didn't see that from the Indian point of view. That it was a war zone where Indian people had no way of defending themselves.

And so, and this, this, this, this was never, never part of the – the scene wasn't set. Alright. It was not set at all.

That this was a war zone and that people had finally tried on some level to defend themselves. This was not it. This was not the scene.

VO

Here Louise echoes the criticisms of Leonard’s attorney Elliott Taikeff, while also underscoring how the judge’s decision to exclude evidence about the violence on Pine Ridge ultimately affected the verdict.

The latter being of course one of the recommendations put forward by the Bureau based on their analysis of the Cedar Rapids acquittal.

Louise Erdrich

So I was just trying to follow the facts. Which you think that a poet wouldn't do [laughter]

But this was a trial. So, and I had a very fancy education, so I thought, I, you know, this is, this is going to be where we see. The facts will -- should come out.

There should be something that connects this tremendously serious crime with Leonard Peltier.

So I listened to – there was a lot about a car, you know, a truck, a van, you know, these, these things all came in and out of the prosecution.

So for every single one of these things, you would have to make a leap of faith. You know, that belongs in church. That does not belong in a courtroom.

But if people are in a mindset where there's a bad Indian, and they're afraid, and they hear drums, and they're, you know, they have that grounding in, um, [pause] in a prejudicial upbringing, which most people, most white people at that time, and a lot of people now still have.

The tendency to look at an Indian person and believe the worst. Of course, you know, they're an Indian. That's how it would have been then.

And it still is now, I mean, you know, look up at what's happening in Northern Minnesota, and it's still the same in many ways.

But, then, what I was piecing together, and saying there's no connection. I mean, this can't happen. There's just no connection. You have to have something that connects.

Um, I was seeing the broken links, and they were closing the links with that grounding in fear and resentment.

The moment of the verdict is one of those emotional divides in my own life where I saw the world one way. And in an instant, I saw the world in a very different way.

[MUSIC UP]

And I don't think we were in the courtroom. I think we were in that large anteroom before the courtroom.

When we found out that verdict, there was a sense of, I say that it was this crushing sense of disbelief.

And there was this shout, that every -- there was this, this, this sort of eruption, a shout that was just like, no, no. Um, and then I left.

I probably, for once, didn't go out and have a drink. [Laughs]

That would have been my normal response at that age, but I think we went to a sweat somewhere in -- at White Earth.

And, um, I, it took a long time for that revision of world, that revision of outlook to become in a sense who I was, and who I tried to be for years after that.

Um, it certainly turned up. That's where I started writing Love Medicine. In that book I think I referred to this idea that everyone that I grew up with has about justice.

That it is justice, but that if you're on the other side of a wall – if you're not white, and you're not in the good people category, anything can be done to you, anything.

And you can't depend on justice.

So that became my outlook. Justice became the focus of a great deal of my work. My first book and then a trio of books that dealt with issues of justice.

So we come to the present day, and we see a justice system that has resulted in the mass incarceration – what is it – 3.5 million people now? And Minnesota, itself, imprisoning more women than all of Canada imprisons, and all of Europe.

We come to a world within a world. Of pain within plenty. Of sorrow and misery within a world of ads that show joyful people, joyful Americans eating, and loving, and drinking, and cleaning their carpets.

This is the world we see, and that is the world we have.

That world where people are forced into a world of shuffling pain. Of misery and neglect. A narrow world.

But I have to say, um, in corresponding with Leonard, that I see someone who has made a life out of that world.

VO

After the break Louise opens up about her friendship with Leonard and the special connection she discovered years after the Fargo trial.

ADVOCACY BREAK

This is Chase Iron Eyes, and you’re listening to Leonard, a podcast about one of America’s longest serving political prisoners, Leonard Peltier.

In the ‘70s my father Wallace June Little, Jr. was close with Leonard. It was a friendship that was made even closer by the tragic events of June 26th, 1975, which both were fortunate enough to survive, unlike their AIM brother, Joseph Kills Right Stuntz.

Today I’m excited to announce that I will be officially joining the Leonard podcast as an executive producer in Season Three, which will guide listeners through Peltier’s prison escape and unsuccessful legal appeals up until the present day.

Every June 26th we remember Leonard. We remember him in our run for freedom here in the Oglala homelands, the Pine Ridge Reservation. We also remember Joe Kills Right Stuntz. And I personally even remember Ron Williams and Jack Coler. I don't think they intended to do what they were partaking in that day.

This is a long war. And Leonard Peltier is just one battle in that long war. Just like Little Big Horn. Just like Wounded Knee. The first Wounded Knee in 1890. Just like Wounded Knee Two in 1973. Just like Standing Rock in 2016, 2017.

We have to keep up the fight. And it's difficult. It’s a hard road. But just think of how hard it is for Leonard. Leonard cannot die in prison. He wants to make his journey in his Homeland. He wants to come home, so he can partake of that ceremony according to his intentions.

And I don't know what to say about Leonard. I don't know how he keeps it together in there, but he's strong. And we all benefit from that kind of unconquerable dignity. We can never lose faith. We can never give up or get weary because Leonard Peltier deserves to be free.

Free Leonard.

Louise Erdrich

We come again to the question of justice, and what kind of justice we have in our country.

Everyone in the world doesn't, of course, does not have our system of justice, which is not a system of justice. It's really a system of punishment.

At this point, in fact long ago, one would say Leonard Peltier has been rehabilitated. Leonard Peltier has become an advocate for his people.

He is distinguished by kindness, by his devotion to art, by his devotion to his family. And, you know, he is a strong, good soul.

At this point he's an asset to the world. So why is he living in a cell? Why isn't he out here contributing the wisdom he's earned? Why isn't he with us?

There's, there's no -- it's, it's senseless.

A lot of people died in the mid 1970s.

And I know that when people pray in Sundances, they pray for everyone. They pray for those agents too, and for their families, all right?

And that spirituality, I hear that every time I'm in a sweat, or I'm with people.

People are praying for the people who have victimized them as well as their families.

We pray for everybody.

You know, I remember being at ceremonies with some of the young men who–[DOG GROWLS]

Here – this is my dog growling. I'm going to put him in– I'll be right back.

Rory Delaney

He's famous now.

Louise Erdrich

Hey buddy–

Rory Delaney

What's his name?

Louise Erdrich

Oh, he's, he's named for the little black pig, Ryoga. Which is in an old anime. And it's my daughter named him.

Rory Delaney

I like it.

Louise Erdrich

So Wahpeton, North Dakota, um, is an agricultural town, but it also was originally that -- it really is still on Dakota, Lakota. You know, it's, it's on the original reservation. It's within the boundaries, and that's what it really should be reservation land.

That's why a federal boarding school was established there.

And my grandfather went to this school. In fact, um, I, I went to the national archives, and found letters where he petitioned the superintendent to let him in.

So you hear a lot about boarding schools. Um, it's, it's really complicated. There are a lot of painful, abusive things that happened, but I'm just going to say my letter from my grandfather said, "Please let me in."

And the superintendent's going, “I don't know Mr. Gourneau.” “Yes, let me in.” So he, he, um, went to -- graduated from Wahpeton Indian Boarding School.

He, uh, my, my mother and my father both taught there. Ended up that – it's been -- it was returned to tribal control.

Anyway, my dad loved being a teacher. That's what he loved. He loved teaching his students, and he taught mostly sixth grade. But at some point he taught third grade.

And I can't remember if this was sixth or third grade, but it probably actually was sixth, because my father had a long scroll, and he had every student who ever was in his class sign this really long papers, scroll of paper.

He used to get cuttings from the -- there was, uh, a printing company in the town, and he would take home all the cuttings from the big rolls of paper.

So you’d get these scrolls. He had a timeline that went all around the room and he had this scroll. So we were looking at, down the scroll one time and every single student he'd ever had.

The scroll is like way – it's so long. It stretches for a very long time.

And we came across Leonard Peltier as a student.

I asked my dad what he remembered. And he said, “You know, I think he was a smart kid with a lot of energy. A lot of energy.” [Laughs]

So it wasn't like he could remember everybody. I don't know what else he might've remembered it or not. I don't know if Leonard remembers him, but he was his student.

There's not much to that story. Except that there's this endless scroll with Leonard on it.

And Leonard's, I do remember that Leonard's signature, uh, you know, kids were just writing their names up, but Leonard's was emphatic, you know, like really, really –

It was like he'd written with, um, a heavier, thicker kind of signature.

So you could tell right even then he was really somebody.

VO

Louise discovered her father’s relationship to Leonard when she started writing to him in the late 90s after the publication of his book PRISON WRITINGS.

Louise Erdrich

Okay. Let's see. I'm going to read to you a few pieces of correspondence. Just a few bits of this.

So, um, I wrote to Leonard on and off once I realized that I could write to him. Because he was a writer.

So, um, yeah, he, he wrote back, and said, um, that he'd enjoyed it. I sent him a story with some laughs in it, and he laughed. He said it was funny.

Uh, and he, um, he said, "I remember you from the trial in Fargo. I remember we shook hands one day, and your mom was with you."

Now I don't remember that. And he remembered about the legal team.

And he said, “Do you realize February 6th – that's the year 2000 – will mark my 24th year of imprisonment?”

And then he says, “well,” I thought this was remarkably graceful. “This is why I think all that has happened to me was not all in vain.”

“Sure. I lost my life / freedom, but through it, I've been able to keep Indian issues alive and brought a lot of awareness to our people all over the world. I'm not sure how much longer I can hold on and continue this battle.”

“My health is not the greatest these days. I have some serious problems that are not visible yet, but in time it will have taken its toll on me and begun to show. But I guess no one can not honestly say I did not give it my all for my people, for our people.”

“All I ever wanted was a better life for our people, my family, and now my precious grandchildren. At least so that they would not have to live the life of hardships and poverty as I have.”

And, you know, this, he says, I really do not want to talk. I do really do not like talking about this because I don't want to seem like I'm whining. [laughter]

God, you're in prison, man. This is like a kind of humility. Like I don't want to even say that I lived in poverty, but now I'm going to drop this subject.

Um, yeah, I think I wrote to him, because I liked his book and then, um, eventually I ended up, um, selling a lot of his books at the bookstore. I just had started it.

VO

Birchbark Books is a small independent store in Minneapolis that Louise owns with her sister. It’s also the setting for Erdrich’s latest novel, The Sentence.

Louise Erdrich

And then, um, from his legal team, I bought a painting, and then we established that, that painting, a portrait of Ka'ish Pah, who is a mutual relative. Um, great, great grand uncle.

He's, well, he's in the 1892 census of the Turtle Mountains. His name is translated as Elevated One.

And, um, it's really, it's got a brilliant background that looks like fall leaves. And this is a very – it's a very well-known portrait that was taken in Washington, D.C..

And Ka'ish Pah is wearing a really styling suit coat with a kind of cravat, you know, a very flowing shirt underneath it with a tie. And he has his hands folded.

He's a beautiful man. And I got to say he kind of looks like Leonard, but his, his suit coat is so, um – it's something that you'd see on a runway, you know.

It's got like a fur trim in the back, and broad lapels. A pinched in waist, and yeah, I've got posts– there are postcards.

My mother has painted -- everybody has painted him, or you know, so it's a very beautiful portrait. Not everybody. My mother has.

So everybody on the Turtle Mountains is related. So after we figured that out, um, we're cousins, and uh, I told him, you know, I'm a Gourneau, I should have established that in the beginning.

My mother is a Gourneau. So everybody then kind of figures out who you're related to. And I'm enrolled on the Turtle Mountains in the Turtle Mountain band of Chippewas.

So, um, anyway, I told him, yeah, my mother's a Gorneau. And she still is the town beauty. She always was the Beauty of Belcourt, and we're all good looking.

And he said, “Yeah. The Peltiers are not bad themselves when it comes to the looks department. I know clear across this country when it came to the Indians ladies, I have turned a few heads. I know a few who have gotten severe whiplash.” [Laughter]

Um, okay. And then we've talked a lot about love, because we just talked about love, and he knew someone that I had a very deep relationship with. And so he said, “okay, is it your heart's immortal thirst for his, or is it spiritual, or what? Just curious.”

Yeah. It's my heart's immortal thirst.

And then he talks a lot about his grandkids, their grades, you know, things that people talk about.

I feel like I've been just rattling on. You guys are really good at not interrupting people. [laughter]

Rory Delaney

We've talked to a lot of lawyers, so that helps. [laughter]

Louise Erdrich

Oh, you have?

Rory Delaney

Yeah, they can go.

Louise Erdrich

Right. So I was going to talk to you also about, well, a couple other things,

Anyway, you know, I was talking about fear. So I was thinking about that. What's the basis of that fear?

Sometimes I think that the idea is that capitalism keeps the world going, you know, keeps the world, the world goes round.

What I think is that humble people, people who really count themselves among everything on earth, all the animals and everything on earth, people who, um, just love the earth, and the people on it, and who are suffering together, sweating together, laughing together. A lot of laughing together.

Those are the people who keep the world going, and they're praying for everything and every one and everybody on earth.

So I was thinking about that. What’s the basis of that fear?

Because for years, I've wondered this: Why do Americans so fear Indigenous people?

Why is there a simultaneous fear of Indians and Indigenous people, and romanticism and what is that?

Was that guilt over what America has done? The genocide, the dispossession.

But what has made the US government so vicious toward Indigenous people?

Wounded Knee. Look at Standing Rock. Look at upstate Minnesota and Line 3.

And American Indians imprisoned nearly at the rate of Black Americans.

And I'm just going to throw this out there, but it seems to me that the American militarized police fear native people in some way, because we represent, even though we don't live in this old way, but we represent something that is absolutely unimaginable.

And that is a world, and a social structure, that was not based on capitalism.

It was a world that was congruent with the limits, the ultimate limits of land and nature.

And there's examples of social structures in which wealth was not like accumulated, and showed off, and property defended, but the value and the honor was in sharing what you'd accumulated.

And there was this idea of the dignity of the common good among people.

And that's what really mystified Europeans when they first encountered Native Americans.

When they encountered Indians, they couldn't understand – like you can't give an Indian something because that person will just share it. They'll just give it away. They won't keep it for themselves.

So, you know, often I hear in – especially in this political climate – there is just no alternative to capitalism. You know, it's flawed, but it's still the best that we have.

And it's just not true. Because an alternative to capitalism, it existed right here for what we now know -- I was just seeing the other day -- we now know was over 23,000 years.

That's how far back, at least at this point, um, scientists have traced the native presence on this continent.

In tribal mysticism, everyone has a place, an origin, so it could have been forever you know. I'm just saying that it existed for all that time.

That these social structures, and these ways of sharing wealth, existed – say for this 23,000 years – and for capitalism, once capitalism dominated this continent, it's taken only let's say roughly 529 years to bring us to the brink of destruction.

But we're talking about Leonard, but anyway, that's what I think the fear is somehow based on this idea that it's impossible to envision another way to live. But it's not. It's been here.

Rory Delaney

So do you think that's why Leonard hasn't gotten a pardon from Clinton, or Obama or, you know, and is there a possibility that President Biden might right this wrong?

Louise Erdrich

I think it could, it could happen. I always, but I always thought it would happen. So I'm just going to say it could happen.

Uh, I think that the FBI, I know now that they lobbied and put pressure on Judge Benson, and I think that they want to keep somehow for reasons that don't make sense to anyone else, they want to keep Leonard there as an example.

And I mean, I've heard people say, well, the FBI is protecting them and their families. They don't want to offend the FBI [laughing]. I don't think so.

I don't, I don't know, but I feel like if it did happen, it would be a tremendous moment for Native America.

It would be a watershed moment where instead of holding Leonard up as an example of this will happen to you, don't defend your people.

Don't um, – well, instead of holding, Leonard's endless imprisonment, which, I mean, you know, you, you've done this on the podcast. Um, how, how many people have lobbied worldwide for him to be released?

So instead of holding him up as a symbol of military vengeance, he should be released as a symbol of what the United States also does, which is, in case after case, America also has got kind people, and people who care about real justice, and people who understand what it means to– I should put that differently.

[MUSIC UP]

The United States also has people who see the world as a complicated place where when someone has stood up – wrongly imprisoned in the first place – but has become a symbol for their people of what you could be.

I mean, he is someone who has suffered with dignity. And now he is someone who could bring enormous healing to Native America.

So I think on that, on that basis, if he was released, it would bring a sense of joy and unity. And I mean, it would make me -- it would make everybody cry.

It sort of makes me cry to think of it, because, [choking up] I look, I look back through those days since 1977.

He'll be released by Jimmy Carter. He'll be released by Reagan. He'll be released by George Bush. He will be released by Clinton. Obama definitely. Obama knows his case.

In fact, Leonard wrote about it in his letters. Look, Obama, you know, read my case in law school, you know.

Over and over.

Trump should release him because Trump is really releasing all these insanely, um, diabolical criminals, and Leonard's not a criminal.

I mean, he's not a criminal. What is he going to hurt anybody? No. So why is he in?

So he can be a symbol of military vengeance.

Do we want that? I know people in the military, and I know that a lot of the reasons people go into the military is not because they want to kill people.

It's because they think somehow the military has many missions, and some of those missions are to help people.

And that's also why a lot of people go into law enforcement.

I know people don't like to hear this.

I know that there are people who are cruel in law enforcement, but I also know there are really good people who want to help people.

Let's make that the face of the military and of law enforcement.

Peacekeepers. That's the face we want.

And Leonard's a symbol of that.

He's also a real person, and he deserves to get out.

He deserves to be with his family. He deserves to be hugged by his people.

He deserves to touch his people, to hear their songs, to walk this earth.

The most important thing for Indian people is to be with each other in a powwow in a setting out in the woods around a fire.

The most important thing in the world is to be embraced and to be part of a group of Indians.

And I felt how important that was. I felt it so many times.

And sometimes when I've felt it I've been looking around and saying, “Yeah, I'm free to be among people and then to go away and to come back.”

And he isn't, but he should be – free to be among people to go away to come back to make a mistake, to do whatever he wants.

He should be free.

ROLL CREDITS

This podcast is produced, written, and edited on Tongva land by Rory Owen Delaney and Andrew Fuller. Kevin McKiernan serves as our consulting producer.

Thanks to Bobby Halvorson for the original music we’re using throughout this series. And thanks to Mike Cassintini at The Network Studios for their engineering assistance, and to Peter Lauridsen and Sycamore Sound for their audio mixing.

Thanks to Maya Meinert and Emily Deutsch, for helping support us while we do what, we hope, is important work.

And thanks, most of all, to Leonard Peltier.

To get involved and help Leonard, find us on social media @leonard_pod on Twitter and Instagram, or facebook.com/leonardpodcast.

For updates and special offers subscribe to our newsletter at mbdfilms.com.

In exchange for signing up, we’ll send you a free copy of our unreleased short podcast BEHIND IRON DOORS.

This podcast is a production of Man Bites Dog Films LLC. Free Leonard Peltier!

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.