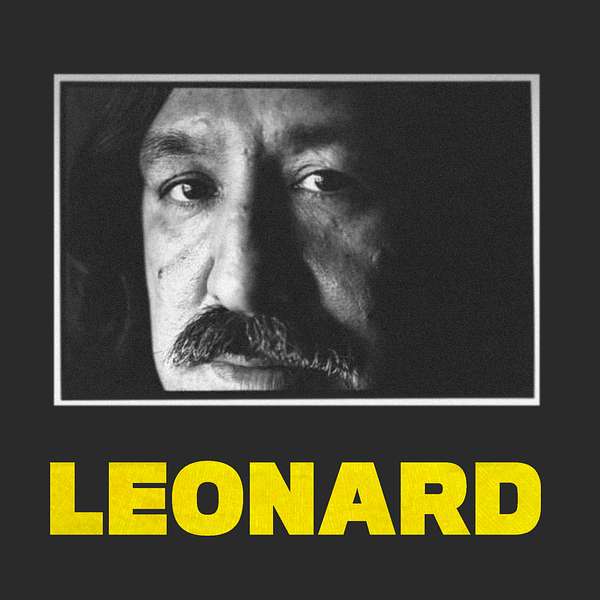

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

In 1977, Native American activist Leonard Peltier was sentenced to consecutive life terms for killing two FBI agents. Then in 2000, a Freedom of Information Act disclosure proved the Feds had framed him. But Leonard's still in prison. This is the story of what happened on the Pine Ridge Reservation half a century ago—and the man who's still behind bars for a crime he didn't commit.

LEONARD: Political Prisoner

Not Guilty

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

We dissect the murder trial of Bob Robideau and Dino Butler who were acquitted by an all-white jury of twelve in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, after a period of intense deliberations that almost resulted in a hung jury and retrial. This is the story of how an all-star defense team, a celebrity peanut gallery, and a plucky community organizing effort combined to produce one of the most unlikely legal victories in the history of the United States.

S2 E11: NOT GUILTY

Prosecutor Sikma

Did Mr. Butler speak about the date that the FBI agents were killed?

James Harper

He said Norman Charles, Norman Brown, Leonard Peltier and some other Indian brothers were at a meeting and they decided when and if agents did come to apprehend Jimmy Eagle they were not going to let it happen without fighting.

VO

This is a dramatization of the testimony of James Harper, the government’s surprise witness in the first-degree murder trial of Bob Robideau and Dino Butler in 1976.

Harper’s bombshell allegations supported the Feds’ ambush theory, which held that Robideau, Butler, and Peltier had lured Agents Cohler and Williams to the Jumping Bull ranch on June 26, 1975, in order to execute them.

Harper’s story was said to be derived from the jailhouse confessions of his cellmate, Dino Butler, who had conveniently and inexplicably spilled his guts to a random wasichu with whom he occasionally played Gin Rummy.

James Harper

They posted a spotter up by Highway 18 and these spotters were instructed to let him know by walkie-talkie if any government cars or suspicious vehicles were seen entering the Jumping Bull Hall residence. And this is what happened around 11:30.

Prosecutor

Did Mr. Butler say what happened?

James Harper

He said that after numerous rounds of ammunition had been fired at the agents that one of the agents was hit and knocked down. I believe he said he was hit in the head and then the second agent was hit and knocked down. After both of them were rendered helpless, they went out – he and the other brothers – and they approached the agents, and that this agent had pled for his life by saying, “I have friends who are Indians” and “I have a family. I don’t want to die.” Dino said, “We wasted him anyway.”

VO

You’re listening to LEONARD—a podcast series about Leonard Peltier, one of the longest-serving political prisoners in American history. I’m Rory Owen Delaney.

And I’m Andrew Fuller. We’ve spent the last four years working to share Leonard’s story with a new generation of people: who he is, how he ended up behind bars and why we believe he deserves to go free.

This is Season 2, Episode 11, “Not Guilty.” In this chapter we put the Robideau-Butler trial under the microscope because it’s impossible to understand Peltier’s ensuing trial in Fargo, North Dakota, without first dissecting the government’s case against Bob and Dino in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

And there’s a lot to dissect. Because the Cedar Rapids trial had everything. Rat finks like James Harper. Hot dog lawyering from William Kunstler. Testimony from FBI chief Clarence Kelley. And a star-studded celebrity peanut gallery made up of Hollywood royalty like Jane Fonda, Marlon Brando, and Bob Redford, plus this one boxer you might've heard of who could float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

All of which is a prelude to a grand finale so dramatic that it feels like it was snatched from an episode of “Matlock,” “Murder, She Wrote” or one of the nineteen spinoffs of “Law and Order.”

Because the government wasn’t the only one with a surprise witness up their sleeve. The defense had one too. And her name was Thelma.

This is the story of how an all-star defense team and a plucky community organizing effort combined to produce one of the most unlikely legal victories in the history of the United States.

Not guilty. That was the verdict reached by an all-white jury of twelve Iowans after a period of intense deliberations that almost resulted in a hung jury and a retrial.

For Bob and Dino it was nothing less than divine intervention – a miracle. And it could’ve been salvation for Leonard, too, as Peltier was originally scheduled to appear alongside Robideau and Butler in Cedar Rapids.

But Leonard was in Canada fighting extradition to the United States at the time proceedings got underway, and so the trial moved ahead without him.

Representing Bob Robideau as his primary counsel was attorney John Lowe, a refined Southern gentleman from Charlottesville, Virginia.

Representing Dino Butler was William Kunstler, a radical New Yorker who became a celebrated pop culture icon in his own right for his rebellious brand of lawyering.

LEBOWSKI

I know my rights, man.

MALIBU SHERIFF

You don't know shit, Lebowski.

LEBOWSKI

I want a fucking lawyer, man. I want Bill Kunstler.

VO

That’s El Duderino being interrogated by the reactionary sheriff of Malibu in the 1998 movie “The Big Lebowski.”

Perhaps the ultimate champion of liberal causes, William Kunstler was a born showman who made his name in the Chicago 7 trial, defending seven activists who were charged with conspiracy after one civilian was killed and 600 were injured during anti-Vietnam protests outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

The case was recently adapted into a Netflix movie starring Sacha Baron Coen, which took home the Oscar for Best Picture at the 2020 Academy Awards.

So, like we said, Kunstler was a legend. And it would take every bit of his charisma, chutzpah and legal savvy to rescue Bob and Dino from a vindictive justice system hell bent on destroying an old foe, the American Indian Movement.

Dino Butler

They went after me because they know that I worked in the National AIM office.

VO

This is a recreation of part of Dino Butler’s conversation with Michael Apted for the Peltier documentary “Incident at Oglala.”

Dino Butler

They went after Bob Robideau because they knew that he was Russel Means’ personal bodyguard at one time.

VO

Means, of course, being one of the best known leaders of AIM, along with Dennis Banks.

Dino Butler

So that’s why they went after us: Because of our involvement with the movement. We were also the oldest: Bob and Leonard and me. And it would probably give them a stronger case to prosecute the older people than the younger people.

VO

Originally, Bob and Dino were due to stand trial in Rapid City in the federal court of Judge Andrew Bogue. But there was one glaring problem with the venue. No one on the defense team believed they could get a fair trial in South Dakota. Especially not the defendants. Dino Butler explained the situation like this.

Dino Butler

In South Dakota at that time the white people’s mentality against Indian people because of the shootout and everything was – was really racist, you know. And I knew that if we went to trial anywhere in South Dakota we probably would get convicted. I mean, all they had to do was just bring us in and charge us, and a jury would convict us. So I was more worried about that than the evidence. I knew that the lawyers could deal with that. But how do you deal with the jury’s racism?

VO

Federal Court Judge Fred Nichol, who presided over the Wounded Knee Trial of Russel Means and Dennis Banks in St. Paul, confirmed South Dakota’s discrimination problem in a report for NPR back in the 1970s.

Judge Fred Nichol

I think the Black man, really, when you come right down to it, the Black man has been accorded more justice in this country, and even with the discrimination that he obviously has, there has been less discrimination against the Black man as a result of what has happened since Martin Luther King started his movement. There has been less discrimination now than there is against the Indians. Now I will admit that I come from a state like South Dakota where you see more Indians, and I really think that in many ways the Indians are worse off than the Black man.

VO

South Dakota’s sitting governor at the time, Richard Kneip, pressed back when confronted on the hot button issue.

Governor Kneip

Oh boy. If there's anything I'd like to reject, it's the one thought I heard: that is that South Dakota was the Mississippi of the North. That is so inaccurate and so wrong that I can't even make a proper correlation or parallel. And while I recognize racial prejudice and racial injustice as a part of society everywhere, not to that extent. And I can’t buy it.

Kevin McKiernan

You don’t feel that racism here with respect to Indian people is any greater than any other state?

Governor Kneip

No. I think it’s perhaps less.

VO

That’s our consulting producer Kevin McKiernan reporting for NPR radio at the time.

According to the Governor, South Dakota was really no more racist than anywhere else, but a followup interview with an anonymous Rapid City businessman from that era tests Kneip’s theory.

Anonymous Rapid City Businessman

I'm prejudiced against what I classify in my own mind as the bad Indian and that's like the drunks and the people I have to put up with down here. And I am definitely prejudiced against them. Now I can't say I'd marry an Indian girl. I’ve went out with Indian girls before and everything, but you know, I really can't say, maybe that was the reason I didn't ever decide to marry one. But my father's a little more prejudiced, I think, than I am. In fact, by far more. Course, I would rather sit next to a clean Indian or a clean Negro any day than sit next to a dirty white person.

VO

These were exactly the kinds of jerks that the Robideau-Butler defense team didn’t want sitting in judgment of their clients.

Because the stakes couldn’t be higher. Like Leonard Peltier, Bob and Dino were each indicted on two separate counts of first-degree murder, the most serious of all homicides.

If found guilty, they were facing the electric chair, so a pretrial motion was made to change the trial venue. Dave Tilsen, who worked as a court investigator for the defense in Cedar Rapids, recalled the process.

Dave Tilsen

One of the things we did was a big change of venue motion, which involved us doing a survey to many thousands of people in Minnesota and South Dakota and all around the 8th Circuit. And we were successful in convincing a judge through our polling and data that they could not get a fair trial in either South Dakota or Minnesota. And the judge moved the Butler-Robideau trial to Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

VO

On the surface it seemed like a win. Until closer analysis revealed that Cedar Rapids was 98% white and that relatives of the slain FBI agent Jack Cohler resided in the area.

In advance of the trial, which took place in the summer of 1976, the Feds launched a scare campaign. On May 11th, U.S. marshals visited every office in the Cedar Rapids Federal Building to deliver a dire warning:

Carloads of AIM terrorists would be descending on the second largest city in Iowa to wreak havoc in the form of shooting incidents and hostage seizures.

This was big news for the cereal capital of the world, which was home to factories for Post, Quaker Oats, and General Mills.

In this sleepy midwestern town folks were more accustomed to the smell of Captain Crunch wafting through the air than gunpowder, so when rumors of Wounded Knee III swirled, folks took notice.

Because of such efforts to poison the jury well, Bob and Dino’s attorneys requested additional time for voir dire. But in a decision that reminded everyone why he had earned the nickname Speedy Eddie, Judge Edward McManus denied their motion, restricting the defense and prosecution to just 24 hours to select a jury of 12.

When the trial finally kicked off on June 6, 1976, the wave of violence that had been predicted by the Feds never made it to shore.

Instead of taking the city by storm, the American Indian Movement established a peaceful camp on the outskirts of Cedar Rapids where sweat lodges were set up and sobriety was strictly enforced.

The Native Americans who attended the trial each day were just as courteous and well mannered as their allies in town but that didn’t stop them from expressing their disapproval of what they saw as a kangaroo court.

When the judge walked in that first morning, many stayed seated in protest of their sovereignty claims, which Dino Butler addressed in his opening statement that we have recreated here.

Dino Butler

Bob and I are members of a sovereign nation. We live under our own laws, tribal and natural. We recognize and respect our own traditional and elected leaders. The treaties that were made between Indian nations and the United States government state that we have the right to live according to our own laws on the land given to us in the treaties. When a person is charged with committing a crime in your society, they are not brought to our society to be tried. We feel we are being deprived of our sovereign rights guaranteed to us by the treaties by being forced to go on trial here in this United States courtroom.

VO

In Dino’s view, because the killing of the FBI agents had occurred on Lakota treaty land, the United States shouldn’t have any jurisdiction in the matter.

And technically the Constitution backed him up. Treaties were supposed to be the supreme law of the land. But that wasn’t going to stop Bob and Dino from being adjudicated. Regardless of its Constitutionality, the trial was going forward.

In their opening arguments for the government the prosecution made the case for first- degree murder, laying out how the killing of Agents Jack Cohler and Ronald Williams on June 26, 1975, had been orchestrated by the defendants in a premeditated ambush.

The Feds’ first witness was FBI Special Agent J. Gary Adams.

Adams testified that around 11 am he had encountered Ron Williams outside BIA headquarters in Pine Ridge where he was conferring with two other agents, David Price and Dean Hughes.

Agent Hughes was there to transport a prisoner to Rapid City for his arraignment. The prisoner was Teddy Pourier, who, along with Jimmy Eagle, was one of the four youths wanted in connection with the theft of a pair of cowboy boots in Porcupine, South Dakota.

Used cowboy boots, or vintage, to use the parlance of our time.

Ron Williams’ former partner David Price was there to follow Hughes in a separate car in case AIM attempted to intercept Pourier. That’s how paranoid the Bureau’s COINTELPRO program was making its own people. They needed two cars to drive a skinny Native American teenager 80 miles from Pine Ridge to Rapid City.

And they needed two cars to drive back out to the Jumping Bulls to see about Jimmy Eagle. That’s what Williams told Adams he was going to do after he met up with Cohler.

At approximately 11:30 am, just thirty minutes or so after their felicitous rendezvous at BIA headquarters, Ron Williams’ initial distress call came in over the radio.

Ron Williams

Hey, we got a problem here. [sound of gunfire] We are being fired on.

VO

This is a recreation of Agent Williams’ radio transmissions that day.

Ron Williams

We are in a little valley in Oglala, South Dakota, pinned down in a crossfire between two houses. [sound of gunfire]

VO

After hearing his friend and colleague was in trouble, Adams raced 15 miles across state lines from his lunch in White Clay, Nebraska to Oglala, South Dakota, where he stopped briefly by Wallace Little’s ranch to put on his bulletproof vest and get out his rifle.

Ron Williams

If someone could get to the top of the ridge and give us cover we might be able to get out of here. [sound of gunfire] Hurry up, or we’re going to be dead men.

VO

Had Adams gone just a little bit farther he would have spied Williams’ car in the pasture below. But a bullet took out his left tire by June Little’s cabin, and he reversed into a ditch while taking evasive action.

The agent’s sobering testimony was intended to support the government’s premeditation theory by suggesting that an ambush had been planned for the 26th after Williams and Cohler had gone to the Jumping Bulls on the 25th looking for Eagle.

But the defense scored an important point when they cross-examined Adams about his own radio transmissions that day.

Specifically Adams was questioned about his report of a red pickup truck departing from the Jumping Bull ranch at 12:18 pm, which was within just a few minutes of when the agents were thought to have died.

This is significant because Agents Cohler and Williams had allegedly spotted Jimmy Eagle in a red pickup truck in the Oglala housing project earlier that morning.

That was of course the inciting incident, which led them to pursue Mr. Eagle onto the Jumping Bull ranch, igniting the tragic firefight.

At 1:26pm Adams made another curious radio transmission. This one about a white and red pickup driven by an elderly Indian man that proceeded into the compound and departed soon after with at least two other passengers.

To the defense Adams’ admissions suggested the existence of other potential suspects. If the agents had pursued a red truck onto the ranch, and a red truck was reported leaving the scene of the crime around the time of the killings, why weren’t the driver and occupants of the mystery vehicle in court fighting for their lives?

It was a point that dogged prosecutors for the remainder of the trial because they had to meet the burden of proof. They had to show that Bob and Dino were guilty of first-degree murder beyond a shadow of a doubt.

After the break, the Feds search for a silver bullet.

ADVOCACY BREAK BY TSIPI BEN-HAIM

Hello, I'm Tsipi Ben-Haim, founder, executive and creative director of CITYarts New York City. You’re listening to “Leonard,” a podcast series featuring the Native American artist Leonard Peltier who has been wrongfully incarcerated for 47 years.

Can you imagine being in prison for one day, one month, one year for a crime you did not commit?

I strongly believe that it’s his vivid imagination that keeps him alive. It’s evident in the art book of his 126 paintings CITYarts recently produced. He painted his people with a human touch and every brush stroke brought their dignity alive.

On his first call from prison to me I said, “I’m so sorry your life was stolen at age nine in boarding schools and most of your adult life in prison.” “But not wasted,” he replied. “My being imprisoned raised awareness to my people and many changes were made.”

It is said in the Talmud, "He who saves one life saves the world." President Biden, you will agree with me, please grant Leonard – 78 years old, suffering from terrible health problems – a compassionate release. This injustice doesn’t belong in America.

VO

One of the prosecution’s more effective witnesses was pathologist Dr. Robert Bloemendall whose graphic testimony highlighted the brutality of the killings.

According to Bloemendall’s forensic analysis, Jack Cohler was the first to be wounded when a high caliber bullet passed through an open trunk door and almost blew his arm off at the elbow, severing the brachial artery in the process.

Agent Williams then took a round in the foot and two more in the arm and side while attempting to use his shirt as a tourniquet for Cohler’s arm.

The doctor went on to describe the fatal close range shooting in detail, explaining how Williams had extended his hand in front of his face in one last defensive gesture before a bullet passed through his palm and blew a hole in his head.

It was then that the gunman turned to Jack Cohler, who was already unconscious from blood loss, and finished him off with a single shot.

The pathologist’s testimony in concert with the Bureau’s grisly crime scene photography pulled on the heartstrings of the jury, but none of it connected Bob and Dino to the close-range killing.

To do that, the government called another witness, one of the AIMsters camping at the Jumping Bulls that summer, Wilford “Wish” Draper.

Draper’s most damaging testimony regarded a conversation he claimed to have overheard on the night of June 26th when Leonard, Dino, Bob, Jean Roach, Norman Brown, Mike Anderson and the rest of the crew were escaping through the night.

En route to Morris Wounded’s house, Draper testified that Leonard had said something like, quote, “I helped you move them around the back so you could shoot them.”

But Draper diminished his own credibility when he acknowledged during the defense’s cross-exam that much of his testimony had been coerced by the FBI.

According to the young Navajo, he had been strapped to a chair for three hours and threatened with life behind bars until agreeing to turn state’s witness. In return Wish was promised exoneration on all charges and a new start in life.

Another witness, which backfired on the government, was AIMster Norman Brown who recounted in our last episode “Dragnet” how the FBI had bullied him into cooperating by terrorizing his mother.

When the Feds put Norman on the stand in Cedar Rapids, Brown stated that all of the AIM men and boys except Wish Draper had shot at the agents on June 26th.

But the defense had never disputed this fact either. Bob and Dino had always admitted to firing on the agents from long range. It was the close range shooting they contested.

As for the incriminating exchange Draper said he witnessed on the night of the 26th, Brown denied hearing Peltier ever make any such admission.

That wasn’t the really embarrassing part, though. The really embarrassing part was that Brown had sworn to a Rapid City grand jury that he had seen Bob, Dino and Leonard near the agents’ cars just before he heard three shots.

That testimony was one of the building blocks of the government’s case. But during his cross-examination in Cedar Rapids Norman did a complete 180 and confessed that that story was a lie.

Truth was he had never seen them anywhere near the agents’ cars. And it wasn’t until days later that he even knew Cohler and Williams had been killed.

The entire experience has weighed heavily on Norman ever since as fellow Oglala shootout survivor Jean Roach explained to us at the Pine Ridge Pow Wow in 2019.

Jean Roach

Norman was fifteen when the shootout happened. His testimony was never really damaging, you know, that came out in Cedar Rapids. But I think the point is that he even talked that people got mad at him. Way back in the 70s, anybody talked, y'know, or even got seen with a Fed or whatever, you're like labeled.

Jean Roach

So he's been healing all this time, you know, and um, we talk a lot, you know. He talks about how that bothers him. Because he was up there on top where they had the shootout at, you know. He was probably one of the younger ones. But he felt like they were bothering him for a while, you know, their spirits.

VO

Another government witness who recanted her statements to the FBI was Myrtle Poorbear.

Poorbear was the mentally challenged woman who swore she saw Leonard kill the FBI agents on June 26th in the company of Bob Robideau, Jimmy Eagle, Ricky Little Boy, Madonna Slow Bear and another unidentified Indian man.

According to her version of events, Poorbear tried to stop Leonard from shooting Cohler and Williams only to be restrained and forced to watch their execution. Myrtle said she then took off on horseback and galloped along the creek back to her car, which was hidden in the trees as part of the ambush’s getaway plan.

Myrtle’s account seemingly tied the government’s whole case together, so it came as a shock when the prosecution withdrew her as a witness at the eleventh hour.

William Kunstler

They don’t want to call her because they know she is a fake.

Robert Sikma

She is not a fake.

VO

That’s Mr. Kunstler and assistant prosecutor Robert Sikma in a dramatization of their courtroom exchange.

William Kunstler

They know she is a fake but they have put us in the position of having worked all weekend on this witness, and I think they should be required to call this witness to the stand. This is part of the offensive fabrication.

VO

The defense alleged Poorbear was a fake because attorneys had discovered the first statement she had given to the Bureau. In that statement Myrtle denied ever being in Oglala on June 26th.

Of course, that first affidavit hadn’t been turned over by the government during Peltier’s extradition trial, which we will detail in our next episode. They had only turned over the FBI’s later interviews in which she claimed to be a first-hand witness to the killings.

But the defense had uncovered the incriminating document and invested considerable resources preparing to rip her testimony to shreds. That’s why her last minute withdrawal was so infuriating. Kunstler again.

William Kunstler

Put her on the stand and we’ll show you she’s an FBI fake. Just as they did in the Means-Banks trial. That is why they are reneging about calling her. They know she is a fake.

VO

The Means-Banks trial was adjudicated in 1974 in the federal court of Judge Fred Nichols, whom you heard earlier comparing the racist abuse faced by Native Americans in the Dakotas to that of Blacks in the South.

Mr. Kunstler brings it up here because a funny thing happened in that trial that’s worth mentioning.

To magically fill in the gaps of that case, the government conjured up another fake from thin air, former AIM member, Louis Moves Camp.

Moves Camp was a last minute surprise witness, just like Harper.

And the Feds would have gotten away with it, too, if not for the meddling defense team, who uncovered video evidence placing Moves Camp in California at the time of the very events that under oath he had purported to witness in South Dakota.

The revelation caused Judge Nichol to dismiss the charges against Means and Banks after he concluded the quote “waters of justice have been polluted.”

The FBI agent who oversaw the fabrication of Louis’s testimony was none other than Ron Williams’ former partner, David Price, the same scoundrel who had prepared Poorbear’s affidavits or 302s in Bureau speak.

Myrtle Poor Bear

Dave Price is the one that really gave me a hard time. [sound of gun cocking] He put his hand like this real fast, and he said that’s gonna be one of these days. You know, the way they talked, the law was in their hands. They could do anything.

VO

That’s Myrtle Poor Bear in the documentary “From Wounded Knee To Standing Rock,” explaining how FBI Agent David Price had pantomimed a gun to infer that if she didn’t cooperate he would kill her in order to get his way.

By withdrawing Poorbear in Iowa, the government was hoping to avoid another embarrassing and potentially disqualifying blunder.

In replacement, they called James Harper, the wasichu who opened this episode by testifying that his former cellmate Dino Butler had confessed to (a) “wasting” the agents and (b) premeditating the whole thing.

The Feds believed Dino’s jailhouse confessions would be the walkoff home run to clinch the game in Cedar Rapids, and so following his testimony, the prosecution rested.

On June 22, 1976, the defense began to present their case to the jury. Their strategy was simple: Show that Bob and Dino’s actions on June 26, 1975, had been undertaken to protect the women and children in their camp.

To convince the jury it was self defense, the team needed to contextualize just how rough and tough life in the 70s was on Pine Ridge.

One of the first to speak on the subject was AIM’s national chairman at the time, John Trudell. Like all of the Native American witnesses who testified for the defense, Trudell swore to be truthful not on the Bible but on a sacred traditional stone pipe that was brought to court each morning and filled with tobacco by Lakota holy men.

Trudell spoke poetically of the bleak poverty and numbing violence that drives so many on reservations to an early grave, explaining how the American Indian Movement was founded to address the cycle of historical trauma affecting Indigenous peoples.

Another prominent witness for the defense was the chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Frank Church, who had formed the Church Committee to investigate abuses by the FBI, CIA, and NSI vis-à-vis their COINTELPRO program.

The Democratic Senator from Idaho testified that his committee had found cases in which the FBI had released false information to discredit activist organizations and foment internal violence within groups like the Black Panthers and AIM.

According to the defense, COINTELPRO, the FBI’s controversial counterintelligence program, was critical to understanding what had happened on June 26th.

Which is why Judge McManus granted their motion to subpoena a sitting FBI Director, something that had never been done before in the history of the United States.

So when Clarence Kelley reluctantly appeared in Cedar Rapids, he became the first Bureau Director to ever serve as a witness in a court trial.

The most impactful moment of Kelley’s testimony came when Mr. Kunstler zeroed in on the ResMurs investigation and why the FBI had responded in such a highly militarized manner.

William Kunstler

Agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation have, among other things, M-16’s, automatic weapons. They have bullet proof vests. There are Army type clothes issued, jackets and so on. That is somewhat different than agents normally have in, say, Cedar Rapids or New York or Chicago, isn’t it?

Clarence Kelley

Yes. That is different.

William Kunstler

And that is due to the fact that the reservation is essentially considered to be more dangerous than Cedar Rapids, Iowa?

Clarence Kelley

More dangerous perhaps to FBI agents, two of whom have been slain.

William Kunstler

Hundreds of Native Americans have been slain, too, haven’t they?

Clarence Kelley

There have been many Americans slain but two FBI agents were slain, too, and I think they have reason to be really concerned about their own lives!

William Kunstler

One of the reasons for equipping them this way is that there is a fear that strangers who come into isolated areas on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation who are not known to the people there might themselves come under attack out of fear. Isn’t that correct?

Clarence Kelley

I don’t care who it is that comes in. If they are threatened they have the right to protect themselves!

VO

FBI Director Clarence Kelley had been cornered into an incredible admission.

Everyone has the right to self defense, especially on Pine Ridge, which in 1975 was the most dangerous place in America according to the government’s own metrics.

Bill Kunstler underscored the implications of the chief’s testimony to reporters outside of the Cedar Rapids federal courthouse.

William Kunstler

It’s not murder. But it was a tragic confrontation prompted by agents or BIA police shooting into the area, and Native Americans who fear massacres as white people fear the plague responded accordingly.

VO

The world was beginning to understand just how fraught life on Pine Ridge was in the 70s and why violence could spark anywhere at the slightest provocation.

That’s because the defense had painted a vivid portrait of the grim state of affairs facing the Lakota traditionals while undermining the credibility of many of the prosecution’s witnesses.

To compensate for their case’s shortcomings the Feds tried to frighten the jury into a guilty verdict by spreading fear in the Cedar Rapids community.

But the women of the American Indian Movement countered the government’s Machivellian tactics by launching a grassroots organizing effort to show the public they were not a gang of militant extremists as folks had been led to believe.

Jean Roach went to Iowa to help with the PR push as she explained to us in May 2021.

Jean Roach

I went with Nilak Butler. She actually picked me up. That was her husband Dino at the time. But before we got there, the FBI put a, um, teletype out that the Indians are coming, you know. [Laughing] Watch out for your belongings. Watch your women. Whatever they say, you know. They gave a warning to the community and really made it negative for us to go in there to go to court.

Nilak Butler

The citizens were just psyched out – totally psyched out.

VO

That’s Nilak Butler recalling the vibe to author Peter Mathiessen in this recreation of their interview for IN THE SPIRIT OF CRAZY HORSE.

Nilak Butler

The headlines at that time were that the Governor was asking for National Guard support during the trial, and that’s where we were going to get our jury. So we went out into the community and explained that our people were only there to be supportive, that there was a certain code of conduct that we still go by and abide by, and what they could expect during the trial.

Jean Roach

So what she did was started organizing with church groups and met with them and told them who we were. And we were gonna need some help. And it really turned out pretty positive.

Nilak Butler

People were really paranoid, really scared, but their attitudes did change. That community became a lot more aware of what is going on, and they were appalled at the illegalities in that trial.

VO

The women’s organizing effort was so effective that on the same day that the verdict would be announced the citizens of Cedar Rapids organized a spontaneous march in support of Bob and Dino.

Also effective was Bill Kunstler’s media strategy. Every day the lawyer was beating the drum for Bob and Dino in the papers. Dave Tilsen again.

Dave Tilsen

Bill Kunstler felt that the more publicity the better for the defendants and the trial. Also the more publicity the better his profile, and some people misunderstood that and thought he was, you know, being an ego and just liked to see his name in the papers and stuff. And what I came to understand is that Bill's organization, the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York City, was a nonprofit law office, and they paid for everything Bill did. He never charged a dime.

VO

To generate money for his non-profit and fund his pro bono legal work, Kunstler was a frequent lecturer on the speaker circuit where universities and other organizations would pay top dollar for him to appear.

By keeping his name in the papers Kunstler stayed relevant and so did his clients. The strategy netted a lot of favorable press for Bob and Dino.

But that wasn’t the master attorney’s only trick. He had another way to undermine the hyperbolic horror stories put forth by the law enforcement community. Celebrities.

Dave Tilsen

The other thing Bill did is he used his network of celebrities and brought them in. Marlon Brando came in. Jane Fonda came in. Robert Redford came in. You know, they sat in the front row. And there was a lot of groupies who, you know, were all excited. "Oh, Robert Redford's coming. Oh, Jane Fonda's coming. Oh, Bonnie Raitt is coming. Oh, you know, Marlon Brando is coming." And I would scoff and tease people.

Dave Tilsen

But then I met my limit when Bill Kunstler invited Muhammed Ali in. Then all of a sudden I was the groupie. I was saying, "I'm picking him up at the airport,” you know. And I did pick him up at the airport and chauffeur him around for the day that he spent there. And he was wonderful. He was a solid human being who cared and did everything he was asked to do to build support in the community for us and for the defendants. People had set up speaking engagements for him. Had set up a luncheon. And when the trial happened, he was in the front row and very skillfully got the jurors to notice him as he hugged both of the defendants.

VO

Nine months after his legendary ‘Thrilla in Manila’ fight versus Joe Frazier, the People’s Champion aka the Greatest strode into court in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and sat in the defense’s corner.

And that was no small deed for the fighter. Ali had recently been confined to a wheelchair as he recuperated from the injuries he had sustained in Tokyo in a martial arts bout dubbed the War of the Worlds.

On June 26th, 1976, more than 1.4 billion people watched on television as wrestling icon and Japanese national treasure, Antonio Inoki, put a vicious beating on Ali, who endured over 100 kicks to his legs over 15 rounds.

The beating was so bad that after the clash Muhammad Ali was hospitalized in Santa Monica, California, where he was treated for two blood clots and a nasty leg infection that had doctors considering amputation.

The point here is that despite serious risks to his health and career Ali made the trip to Iowa in order to quote "bring attention to what they're doing to the Indians there.”

The surprise court appearance by Sports Illustrated’s Athlete of the Century was an uppercut that left the government dazed and clinging to the ropes.

After the break, the defense lands a knockout blow in the trial’s final moments.

ADVOCACY BREAK TWO BY EVE 6’S JONATHAN SIEBELS

This is Jonathan Siebels, guitar player for Eve 6, and you’re listening to LEONARD, a podcast series about America’s longest serving political prisoner, Leonard Peltier. Leonard’s imprisonment is part of a long genocidal war the U.S. government has waged against native people. Every day he spends in prison is unacceptable. But we can change this. Right now there is a letter on Joe Biden’s desk from seven senators asking for clemency for Leonard. Biden could grant this at any time, and he should. You can text President Biden daily and ask him to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier at 302-404-0880. I’m calling on Joe Biden to grant clemency for Leonard Peltier. Free Leonard and all political prisoners.

VO

The knockout blow for the prosecution came from an unlikely source, Mrs. Thelma Hess, a missionary and housewife, whose testimony we have dramatized here.

William Kunstler

Did Mr. Harper have occasion to comment to you anything about this case where two Indians were accused of killing two FBI agents?

Thelma Hess

Yes, he did. He watched all the news, read all the newspapers. He knew the people’s names. Even briefed me on it. Even the people I didn’t know. He would say, “Now listen to this.” He was studying night after night, and would say that this was cool, this person would waste that person, things like that, and he seemed to be studying it constantly.

VO

As luck would have it, while Dino Butler’s former cellmate and gin rummy partner James Harper was out of police custody awaiting to appear in the Robideau-Butler trial, he was living at Thelma’s house, working with her husband and generally running his mouth.

William Kunstler

You contacted the attorneys for Mr. Butler and Mr. Robideau this morning, didn’t you?

Thelma Hess

I called the Roosevelt Hotel and asked for somebody on the defense side, yes.

William Kunstler

Why did you do that?

Thelma Hess

Well, the other day I didn't know anything about this case, and I didn't know anything about James Harper’s testimony until another person asked if I had read Jim Harper’s statement. And I went back and found the paper and read it. And in Jim’s wording about wasting this person and wasting that person, I recognized they were the things that he told me. That if he ever got picked up that he would waste somebody. He didn’t care who it was, whether it was a jailer or an inmate. In fact, he said, “Hopefully I can find somebody that is a no-account in that jail. A queer or a rapist. Wouldn’t make any difference whether they were wasted or not.” He even told me that he would give information on anything. He didn’t care how close a friend it was he was going to hurt. He was going to turn state’s evidence against other people. Then he could get the Federal agents interested in the Texas case.

VO

James Harper cut a deal to avoid being extradited to Texas where he was wanted on charges of theft by fraud. He was a fake.

But how had Harper been able to go into such minute detail about June 26th? Dino Butler answered the riddle when he spoke to Michael Apted in 1990.

Dino Butler

I remember when James Harper came into jail there. He was a very likable person. He liked to talk to people and things like that. But at that time, I wouldn’t talk to anybody that I didn’t know inside those jails. I would play cards and stuff, but we would never talk about nothing.

And James Harper came in there, and I remember he kept coming up to me, offering me cigarettes and wanting to talk, trying to become my friend, you know. And I would listen to him. I wouldn’t be rude and tell him to leave me alone. I’d just listen, you know.

And he kept that up, so after a couple of days, I finally said, “Well, hey, man, anything you want to know about my case,” I says, “Here.” And I threw all these papers down in front of him that the lawyers had been bringing in to us, you know.

And I said, “Whatever you want to learn is in these papers, so just go ahead and read them.” He did that for two days, man. And I didn’t think nothing of it. And that whole time he was talking to FBI agents about me confessing to him. And he made up a story. And they used him. I didn’t say nothing to him.

VO

In his closing statement John Lowe argued that much of the evidence that had been supplied by prosecutors implicated others more than his clients.

According to the defense, the evidence suggested that Joe Stuntz and his brother-in-law Norman Charles were more likely to have finished off the agents than Bob and Dino.

Joe was the one found dead in an FBI swat jacket. Plus, Stuntz and Charles were among the first ones on the scene when gunshots rang out. Bob and Dino, on the other hand, had been down in Tent City where they were anticipating a lazy pancake breakfast per the testimony of Norman Brown.

The Feds tried to tout Bob Robideau’s fingerprints on the driver’s side door of Williams’ vehicle as circumstantial proof of his involvement in the homicides.

But just because Bob was in one of the agent’s cars didn’t prove he had killed anyone. After all, Bob, himself, had admitted to moving Williams’ vehicle back to their camp in Tent City. That’s where it was scavenged for supplies by the AIMsters who believed at the time that they would never escape the situation alive.

Then there was the whole question of the two red pickup trucks that Agent Adams had reported entering and exiting the Jumping Bull ranch around the time of the killings. Who were in those vehicles? And why hadn’t they been investigated?

By suggesting alternative narratives, Mr. Lowe was seeding doubt into the mind of the jury, but ultimately, their decision came down to a question of self-defense.

On the subject Judge McManus delivered these important instructions.

Judge McManus

In order for the defendant to have been justified in the use of deadly force in self-defense, he must not have provoked the assault. If the defendant was the aggressor, he cannot rely upon the right of self-defense to justify his use of force. To claim self defense, the circumstances under which he acted must have been such as to produce in the mind of a reasonably prudent person, similarly situated, the reasonable belief that the other person was then about to kill him or the Indian women and children, or to do them serious bodily harm, and that deadly force must be used to repel it.

VO

After five days of deliberation the jury was hopelessly deadlocked and begged the judge to declare a mistrial. But Speedy Eddie sent them back to their chambers.

Robert Bolin

Well, we started out with eight for conviction and four against. By the middle of the week we had about six and six. On Friday morning, it was still like maybe eight and four in favor of conviction. It was a long haul.

VO

That’s jury foreman Robert Bolin recounting the painstaking process in a recreation of his interview for “Incident at Oglala.”

Robert Bolin

There was three people that were key: myself and two other engineers from Rockwell, Murray Goldmatt and Jules Yoder. And the three of us kind of teamed together and said, hey, we gotta get this thing going, or we’ll be here for the rest of our lives.

And we kind of got together and teamed up to – to convince the holdouts. And we felt very strongly that the evidence very logically said that they were not guilty. And so we decided we’d try and see if we couldn’t get this trial over with and bring in that not guilty verdict.

Finally, the thing that really swung the hold-outs was, number one, there was no ballistics evidence. The prosecution tried to show that the guns that Butler and Robideau had might have fired the bullets. Okay. He’s carrying something that fires a certain type of bullet, which they found at the scene. But they couldn’t actually tie any of the found bullets to any one specific weapon.

So that kept the government from positively identifying Robideau or Butler as being the ones pulling the trigger. And they had no other evidence. Nobody saw them there. The only sighting that the jury believed for sure was the sighting that they were a hundred or two hundred yards away hiding behind a car firing their guns.

That was the only positive evidence that we had that Robideau and Butler actually fired on the agents. And the mass confusion of what was happening down there tended to help the defense in their theory that Bob and Dino were just on the reservation, and they were caught in the firefight, and yes, they were shooting, but they hadn’t planned it, and there was no proof that they were the ones that went down and did the final close-in shooting.

VO

When the jury returned with a decision on July 16th, 1976, the Native American community was feeling optimistic about Bob and Dino’s chances.

That’s because revered Lakota medicine man Selo Black Crow had prophesied that all would go well if a string of four thunderstorms hit the area during their deliberations.

Lucky number four drenched the town just a few hours before the verdict was reported. Dino Butler recalled the tense moments before he learned his fate.

Dino Butler

I remember the lawyers telling us to watch the jury when they come down. If they look at you, or if they smile or anything like that, then we’re probably okay. But if they just completely ignore you then we’re in trouble. So I was watching the jury when they come back in, and sure enough, every once in a while one of them would look over when they were walking by, or one would smile, you know. And when they read the verdicts like that, it was – it was beautiful. That’s a freedom that people don’t really realize too much in their lifetime.

VO

The foreman Robert Bolin was tasked with reading the jury’s decision into the official record. He relived the scene for Michael Apted.

Robert Bolin

When we got to the verdict, I thought the U.S. marshals were going to kill all twelve of us on the spot. I had the feeling that they were going to kick me down the stairs. You could just feel the tension. They were mad. And they hated every one of us. It was obvious.

VO

The not guilty verdict was widely reported in the media and even made the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

Walter Cronkite

In Cedar Rapids, Iowa today a federal jury acquitted two members of the American Indian Movement of charges that they murdered two FBI agents. Robert Robideau and Darelle Butler had been accused of the killings during trouble last summer at South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation.

VO

If the most trusted man in the news reported on something, people took notice. Especially at the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, DC.

For the upper brass in the FBI the not guilty verdict was an unacceptable outcome.

To pinpoint where things had gone wrong for them, the Bureau ordered a post-mortem on the trial, which began within a few days of the jury’s decision.

Robert Sikma

I wasn’t totally surprised by the verdict, because that trial, as trials go, really got out of hand.

VO

Assistant prosecutor Robert Sikma blamed the verdict on an atmosphere of fear and intimidation that he claimed was created by AIM in this recreation of his interview for “Incident at Oglala.”

Robert Sikma

The jurors complained throughout the course of the trial, and those complaints were made known to the judge: That AIM members were driving by their houses. Were seen by their houses. Individuals had asked questions about them in their neighborhoods. So imagine yourself in a position where you’re sitting on a jury, and the case involves very brutal killings, and there are a number of people supporting the people who are charged with the commission of that offense. Now, the people that are supporting the people who are being charged with that offense are driving by your household, or your children are playing in the neighborhood. They know all about who you are, who your family members are. Regardless of whether these people have any intention of doing anything wrong, just by their proximity, they’re going to have an effect on that jury.

Robert Bolin

That’s totally absurd. Not one person on the jury, including myself, ever recited any incident whatsoever where they even saw an AIM person. We wondered where all the Indians were. We had heard all this stuff about, hey, there’s supposed to be all these Indians all over the place. I didn’t even see any outside the courtroom… The verdict was brought about by a very intense logical procedure. Reviewing of all the evidence. Lots of discussions.

[MUSIC UP]

Robert Bolin

We felt that the acts of the two defendants in the heat of passion was not unreasonable in self defense. And that really was one of the keys. Because if it hadn’t been that the shooting was in self defense, or it could have been shown that they were purposely shooting, then they would have been guilty on the basis of aiding and abetting. And that was explained to us very carefully, too, that with aiding and abetting, not only did they have to be shooting at them, they had to be willfully doing it to help the murderers.

My understanding was that the defendants were probably in a tent area where they were camped when the firing started, that there were women and children in the houses around the area where they were staying, they had young kids with them in their camp, and there was very good reasons to be off with their guns to see what on earth is going on when all the shooting started.

VO

The self defense argument checked out. At least that was the opinion of the foreman of the jury, who was hardly a political extremist.

Bolin worked as an electrical engineer at Rockwell Collins, a fortune 500 company that designed short wave radio equipment for, among other clients, Uncle Sam. So while he might have been a little smarter than your average bear, all things considered, he was a pretty normal dude.

This was a guy who didn’t want to be there anymore than anyone else. Who tried to get out of jury service by expressing concerns that the trial would interfere with his family’s summer vacation plans. But he showed up and performed his civic duty anyway.

The point being this isn’t us extrapolating here. This is straight-from-the-horse’s-mouth, behind-the-curtain-type-of-stuff that explains how and why a jury of 12 arrived at their historic verdict.

When Michael Apted asked Mr. Bolin if he thought the government had a clear idea of what happened on June 26th, his answer was unequivocal.

Robert Bolin

I don’t think the government had a clear idea of what happened basically because of the case they presented. They picked on two guys who they really didn’t have the proof to make the case for them and convict them. I would have thought that after the Cedar Rapids thing they would have dismissed charges against Leonard Peltier and saved the taxpayers some money. To me that would be the logical thing to do. I know our federal government is not always logical, but I believe if Peltier had been tried in Cedar Rapids by the same jury he would have been found not guilty given the same evidence… How could he be anything else?

VO

That would have been the logical thing to do. But the Feds weren’t in a logical frame of mind. They were furious, embarrassed and desperate. They had to save face. They had to set up a rematch. They had to get Leonard Peltier back from Canada.

CREDITS

This podcast is produced, written, and edited on Tongva land by Rory Owen Delaney and Andrew Fuller. Kevin McKiernan serves as our consulting producer.

Thanks to our cast: Matt Babb, Mike Cazantini, Courage the Actor, Charles Krezell, Nate Porter, Chuck Banner, Carolina Hoyos, Rich Palmer, and Elizabeth Saydah.

Thanks to Bobby Halvorson for the original music we’re using throughout this series. And thanks to Mike Cassintini at the Network Studios for their engineering assistance, and to Peter Lauridsen and Sycamore Sound for their audio mixing.

Special thanks to Maya Meinert and Emily Deutsch for helping support us while we do what, we hope, is important work.

And thanks, most of all, to Leonard Peltier. To get involved and help Leonard, find us on social media @leonard_pod on Twitter and Instagram, or facebook.com/leonardpodcast.

This podcast is a production of Man Bites Dog Films LLC. Free Leonard Peltier!

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.